Even in the best of times, handling and transporting big sums of cash can be a messy, inefficient and downright risky business. And in the worst of times? Well, consider what Loomis, Fargo & Co., the nation’s No. 2 armored-car company, experienced this past September. In the space of a few days:

- An armored transport caught fire while carrying 39,000 pounds of quarters (worth $800,000) to a Loomis cash and coin processing facility in Birmingham, Ala. The coin bags burned, and many of the approximately 3.2 million quarters—fresh from the U.S. Mint in Philadelphia—spilled onto northeastern Alabama’s Interstate 59, which was partially closed for 12 hours.

- After Hurricane Katrina, Loomis’ New Orleans cash vault was flooded. Members of the National Guard were sent to retrieve the company’s soggy cash and coins.

- In Las Vegas, former Loomis driver Heather Tallchief walked into a federal courthouse and surrendered to a U.S. marshal. She had been missing since Oct. 1, 1993, when she was said to have disappeared in Las Vegas with a Loomis truck carrying $2.5 million in cash. The money has yet to be recovered.

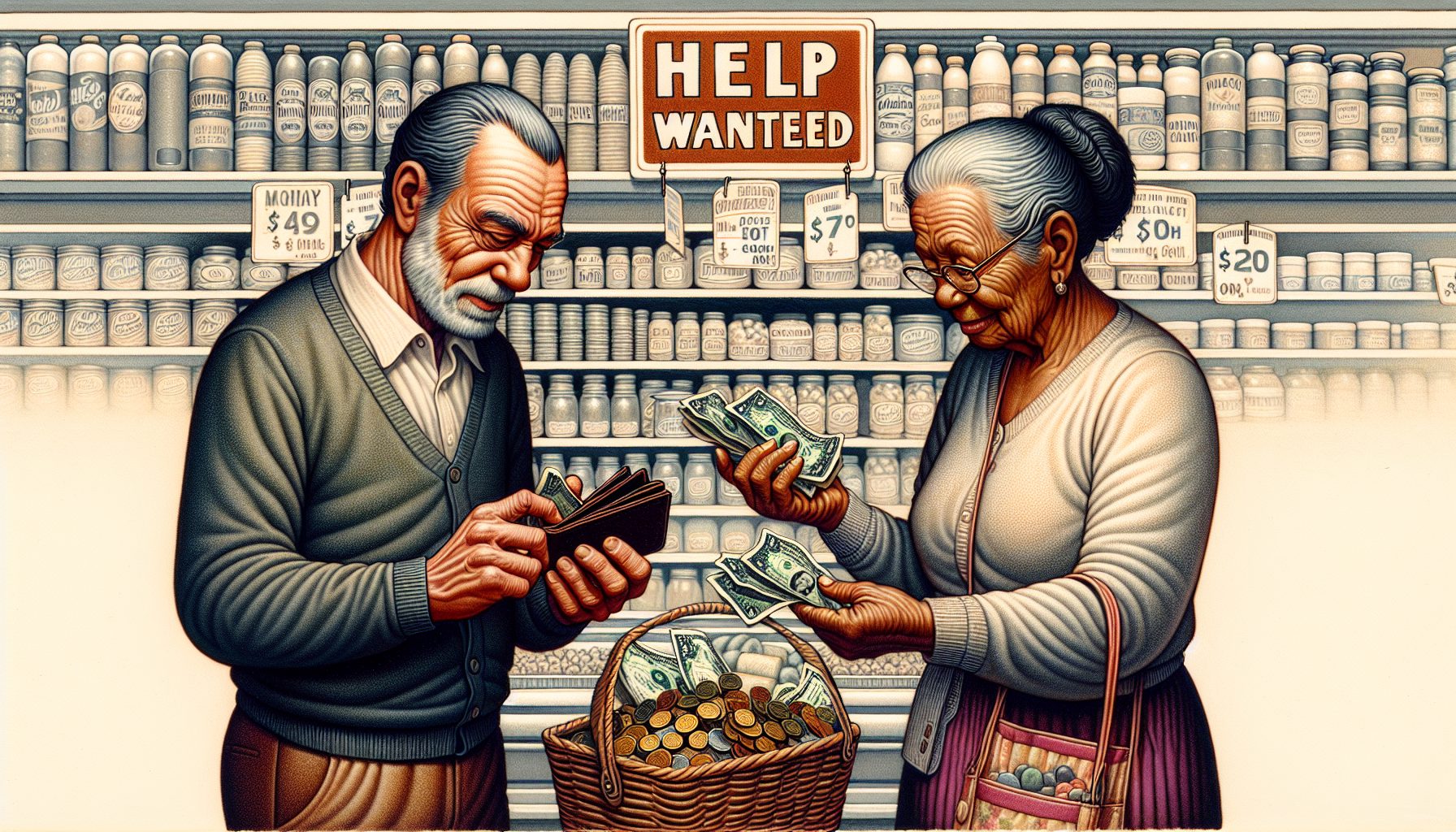

So much for the many predictions over the years of a “cashless society”—and a steady increase in the number of electronic payments. Today, there’s more cash in circulation than ever. On the last day of 2004, according to the Federal Reserve System, the volume of U.S. currency in circulation swelled to 24.2 billion notes, an increase of more than 45% in 10 years.

The Federal Reserve, banks and retailers spend about $110 billion a year processing this cash, according to Marianne St. Denis, an independent cash-handling consultant who says that she has worked with major armored-car carriers and financial institutions. That figure includes cashier and teller salaries, back-room cash counting operations, armored-car pickups, bank processing, and trips to and from the Fed.

These money-handling costs are passed by banks and retailers to corporate customers and consumers, according to St. Denis. “You and I pay,” she says.

Loomis’ chief executive officer, Clas Thelin, says there’s a better way, and—if his dream is realized—it could reshape the way cash is handled in this country.

He would like to see Loomis one day manage cash for retailers with safes on store premises that count cash and electronically credit their bank accounts. He would like to see Loomis manage check-processing and check-clearing functions for banks with new computerized imaging systems.

And, most ambitious of all, he would like to see the company use its nationwide cash facilities and Internet ordering system to take over the Fed’s job of storing and dispensing cash to the nation’s financial institutions.

“Our long-term vision is to manage cash in society,” says Thelin, who was hired in 2004 to combine Loomis with the European cash-handling business of parent company Securitas.

Much, however, has to happen before Thelin’s dream can become a reality. The Federal Reserve, for instance, has said flatly that “currency processing will continue to be performed within Fed facilities.”

But Thelin’s argument is that U.S. currency could be processed by outside companies that can sort and store cash closer to where it is needed—the way cash is managed in Sweden and other countries—which would make pickup and delivery more efficient. Securitas, Loomis’ $8 billion Swedish parent, now processes most of the cash for the central bank in Sweden, and about 40% of the cash in the United Kingdom through a consortium with Barclays and HSBC banks.

Over the last five years, Loomis, to support future needs, has been slowly computerizing its operations. In addition to its Internet ordering system, which allows customers to do business instantly with Loomis over the Web, it put in a software package, called Glory, that allows it to electronically track the cash it stores for customers in its vaults.

And it’s examining the deployment of a wireless system that would allow its drivers to electronically record pickups and deliveries while they’re out on the road.

But the company will need to put other pieces into place, especially if it wants to sustain any competitive advantage it may have achieved against its rivals, say St. Denis and other experts.

One job will be automating a currency handling operation—everything from picking up and delivering cash to tracking money in its cash rooms—that is still based mainly on human sweat and paper strips.

Loomis managers, for instance, hand the drivers of its armored cars paper lists with the day’s pickups and deliveries; when the drivers return, they fill out paper logs to report what they did on their route.

The company has no computerized means to monitor the majority of the cash it transports. Money delivered to most Loomis cash handing facilities is tracked by paper slips—and queries with customers are sometimes settled only after a Loomis employee has rifled through a storeroom of discarded bank bags to double-check that every one of the sacks in a pickup was counted correctly.

And, despite its Internet ordering system, 85% to 90% of Loomis’ customers still call or send faxes to get their cash picked up and delivered—although the company says most major clients use the Internet system.

“The thing we’ve seen in the past, from a global perspective, is that armored-car companies are not good technology innovators or even adopters,” says Bob Blacketer, director of consulting at Carreker Corp., a currency management software and services firm. Blacketer says he has done work with most major armored transport services, including Loomis, Brink’s and Dunbar Armored.

This is the job that confronts the company’s new information chief, vice president of information technology John Jordan. The company had a chief information officer, Mike Grochett, but he was let go in an October reorganization designed to align Loomis more closely with Securitas’ information-technology operations in Europe.

Adding to the cash transporter’s challenges is the sheer size of the U.S. banking industry. As of June 30, the country had 7,445 insured commercial banks, according to the Federal Reserve—more than 60 times as many as Sweden.

Thelin, however, has little alternative but to find new ways to grow profits.

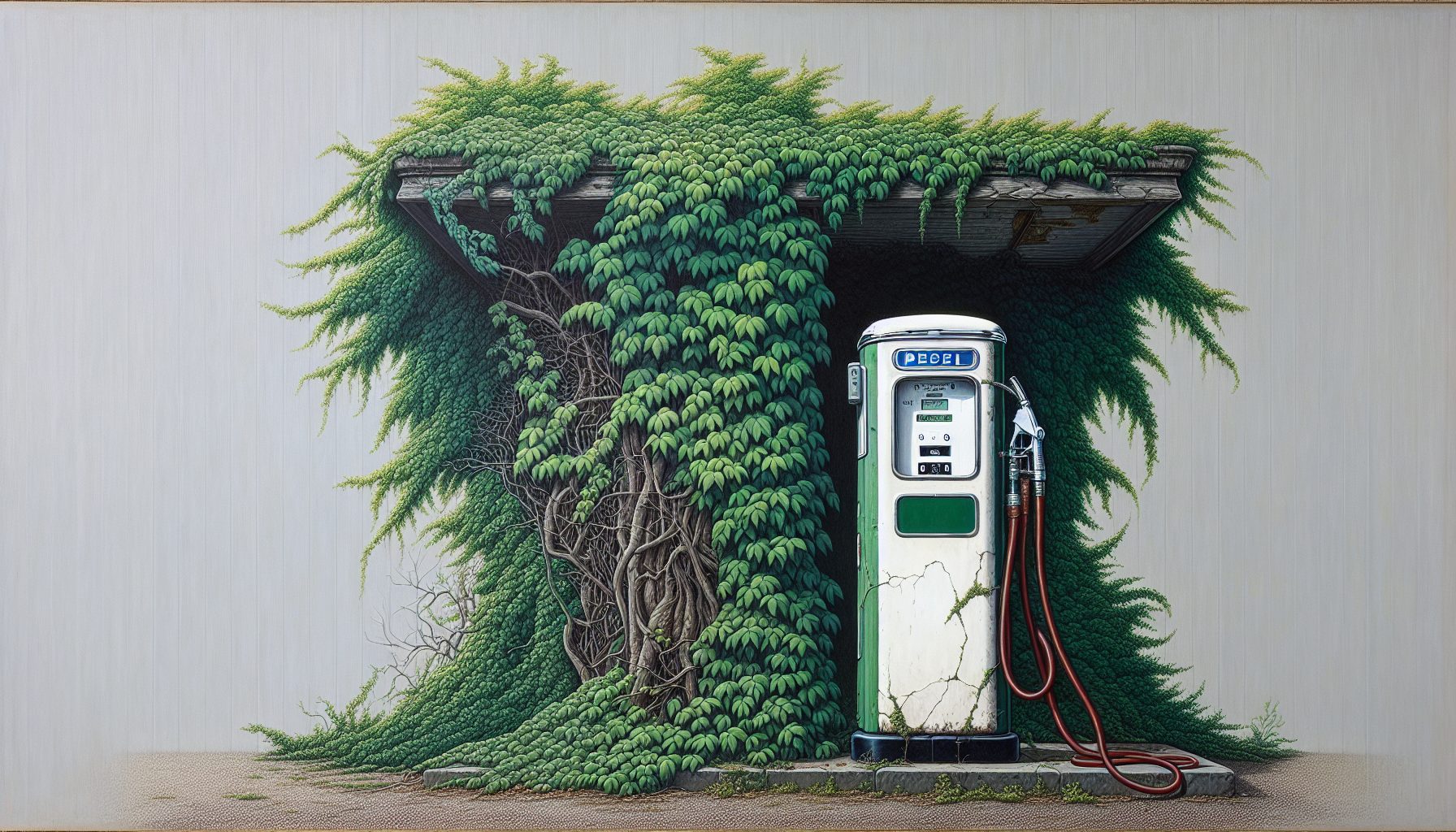

Many armored-car companies think in terms of quarter-to-quarter revenue, so they constantly underbid one another, according to James Dunbar, founder of Dunbar Armored, a competitor to Loomis. In the last 10 years, he says, customers started hiring purchasing agents who choose a cash carrier strictly by lowest bid. “It’s very competitive and cutthroat,” Dunbar says. The result? Some Las Vegas casinos pay a higher daily rate to have their trash hauled away than to have their cash transported to the bank, says Larry Charlton, chief operating officer of the Business Bank of Nevada. “The armored-car industry has done it to themselves,” Charlton says.

Revenue from 2001 to 2004 for cash handling in the U.S., Securitas’ largest market, increased from $417 million to $499 million. But looked at in Swedish kronor, there was a drop of 17% between 2001 and 2004—from 4.4 billion kronor to 3.65 billion kronor. The drop is not seen when revenue is converted into U.S. dollars because of fluctuations in currency rates.

At the same time, Loomis’ costs, like those of the other carriers, have risen. The cost of gas alone has more than doubled—and many of Loomis’ 2,700 vehicles run on $3-a-gallon diesel fuel and get about nine miles per gallon.

The “five-year vision” that Securitas laid out in 2001 when it bought Loomis turned out to be wildly optimistic. For example, operating margin—the amount of money earned before interest and taxes divided by sales, a measure of efficiency—was supposed to reach 15% for the combined cash handling business in 2005, but stood at 7.1% in 2004 and 6.3% as of June 30, according to Securitas annual reports. Thelin calls the growth in the U.S. “a disappointment.”

Further pressure comes from the fact that Loomis isn’t alone in trying to reshape the way money is processed and distributed. Brink’s won’t comment on its cash tracking plans, but Dunbar says it already outfits its drivers with mobile computer devices for tracking trucks and drivers.

A key to competing successfully, says Robert McCrie, a professor of security management at John Jay College of Criminal Justice in New York who has followed the industry for more than 25 years, will be automation throughout the cash transport and processing facility.

Loomis, especially with its Internet ordering system, has successfully tackled some big pieces of the technologies needed to increase efficiency and make progress toward realizing Thelin’s vision. And, as McCrie points out, the systems in place, although manual in spots, could accomplish his goals.

But just as Federal Express gained an edge in the shipping business when it started to keep tabs on packages throughout its enterprise, cash processing companies that can let their customers know exactly where their money is will have a leg up on the competition. “A system with compete visibility will have benefits,” McCrie says. “They ought to be able to track their pickups, which are, after all, much more valuable in terms of money measurements than most FedEx deliveries.”

The bottom line: While the Fed says it has no plans to alter the way it processes cash, experts such as Carreker’s Blacketer say changes in the way the Fed, banks and retailers handle cash are coming and may radically transform the cash handling and transporting business.

“For the armored-car carrier, this could be a huge opportunity,” he says, “or, in the next four or five years, it is going to put some out of business if they do it wrong.”

Story Guide:

Main story:

- Making Change: It costs $110 billion a year to move cash around the country; there’s got to be an easier, cheaper way.

- Most Logistics Problems Involve Less Shooting: Cash carriers that handle automation wrong could go out of business; but forgetting real-world dangers could get people killed, too.

- Automating a Cash Warehouse: The place has computers, but the real work is done on paper.

- Jumping Through the Fed’s Hoops: Pickup and delivery is inefficient enough, but add in a few extra stops so the Fed can keep an eye on things, and you add days of delays.

- Vital Stats: Loomis, Fargo & Co.: Company size, challenges, goals, and how it will measure its progress.

- Player Roster: Who’s moving, who’s shaking and what they’re shaking up.

- Base Technologies:What they’re using to do what they’re doing, and what they’d use to do it better.