Many of the nation’s key defense and security agencies are running their operations on software from companies based outside the U.S.

The Department of Homeland Security uses R/3 resource-planning software from SAP. The German developer says other U.S. agencies, including the Defense Logistics Agency and the Army, also use R/3 or components of the suite, which includes tools to help with everything from accounts payable and receivable to inventory management.

SAP isn’t the only overseas-based software company serving our guardian agencies. The Coast Guard is a customer of software toolmaker Ilog, a French company. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention use software from German database-systems supplier Software AG. And the State Department started work in 2002 on a terrorist-threat database with a number of companies, including Franco-American software maker Business Objects.

But should American security and defense services be buying software from foreign software suppliers? It’s a question that, according to Gartner Inc. vice president and research director Richard Hunter, “is being raised in a lot of quarters.”

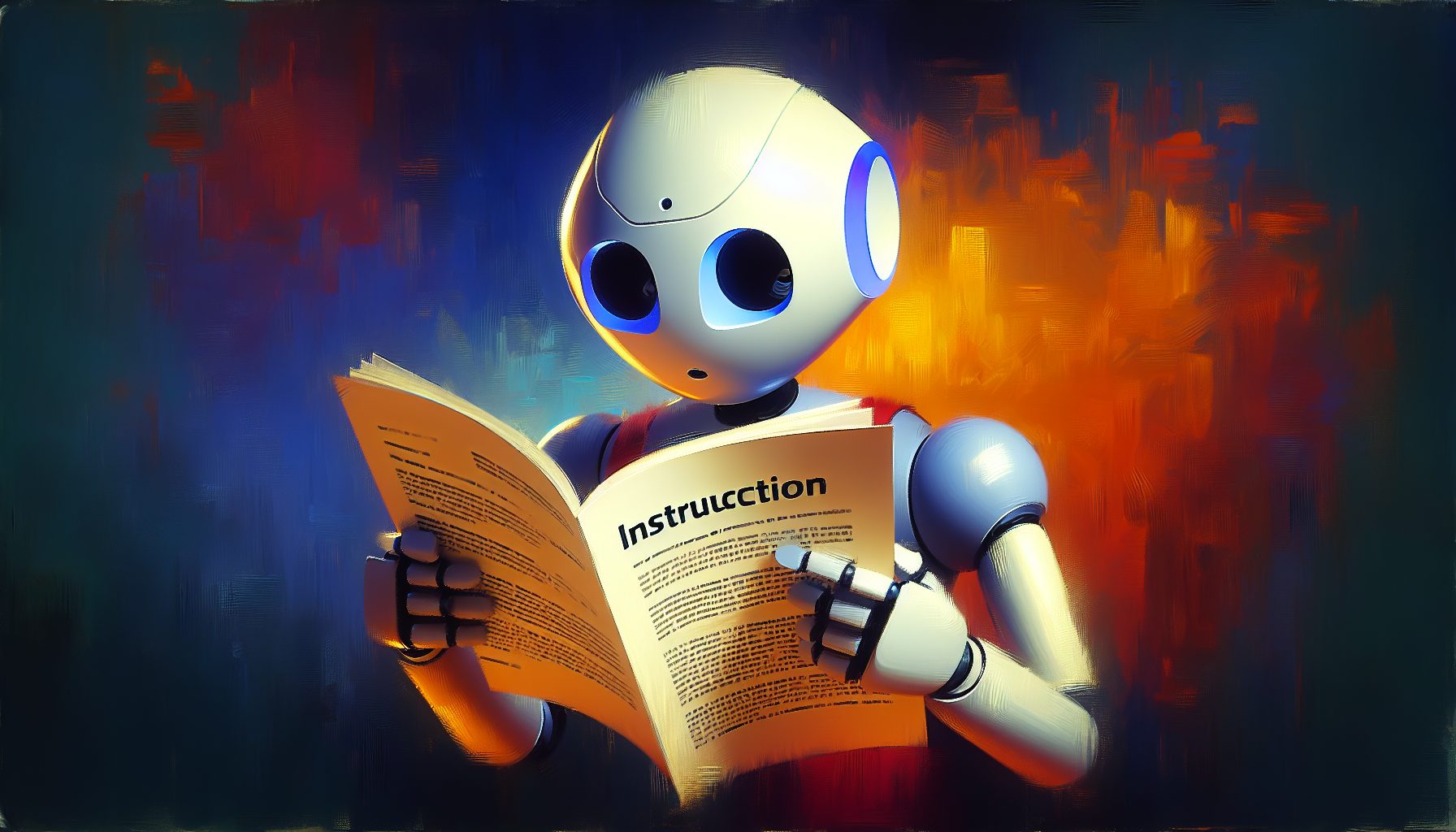

Software experts say it’s unlikely a cyber-terrorist could contaminate a piece of commercial code, because of the security vendors build into their products. But the experts don’t discount entirely this seemingly remote possibility. One can imagine a rogue programmer in Europe or Asia putting “backdoors” or “logic bombs” into a software package. A backdoor is a piece of code that allows hackers access to a system by simply hitting a few keystrokes; a logic bomb is a program that can be set to release, at a specific time, malicious code capable of eating or corrupting files.

Two years ago, Gartner and the U.S. Naval War College poked about to find soft U.S. information-technology targets, and discovered that the security around the servers in commercial software-development shops was “not extremely strong,” Hunter says.

“Assuming you could get the access,” he says, “you could do a lot of things.” As hackers prove with each new virus, no system is impenetrable.

Pradeep Khosla, who heads the electrical- and computer-engineering department at Carnegie Mellon University, notes that any programmer with evil intent can take advantage of software vulnerabilities. Indeed, Khosla and Hunter think it’s dangerous to focus solely on geography when assessing a possible threat. Timothy McVeigh, after all, showed the world that American terrorists are capable of wanton destruction.

“Threats can come from anywhere,” says Khosla, who believes packages from foreign-based vendors such as SAP or Ilog present no more of a threat than the software made by home-based companies such as IBM or Microsoft. And while arguments can be made that the U.S. government is capable of running deeper background checks on suspicious U.S. programmers and that terrorists are far more likely to come from outside our borders than from within, the experts point out that SAP, Software AG, Ilog and Business Objects and the like obsess over security—they have too much to lose if something goes wrong. None of these companies returned calls for comment.

But consider this: Many commercial software programs come together as chunks, with pieces developed all over the world. “It’s not possible to parse out pieces of it,” says Harris Miller, president of the Information Technology Association of America, a trade group representing U.S. technology makers. As a result, he says, it’s next to impossible to determine with certainty where code originates.

And, according to Khosla and others, the tools haven’t yet been developed that can ferret out deeply entrenched backdoors and logic bombs. He says the government does not need to worry about tried-and-true systems such as R/3, but it does need to be concerned about finding ways to develop powerful vulnerability-reduction and malicious-code-detection tools so they can dig deep into code of any origin.

Hunter says all U.S. agencies can do is stay vigilant and “hope for the best.” The only alternative: wait for someone, somewhere, to show the U.S. how to open a backdoor.