If all projects were the same, life would be easy. Whoever ran one project could be handed the next, with success virtually ensured. In reality, projects vary widely, as do the skills needed to manage them—so argue three professors in “Managing Project Uncertainty,” a Sloan Management Review article (Winter 2002) that postulates a continuum of threats, from variation to chaos. Below, we outline the threats, using Baseline case studies to show how managers performed in the real world. (Some did superbly; others flunked.) To get a sense of the threats your project faces, take our quiz.

THE THREAT

Variation

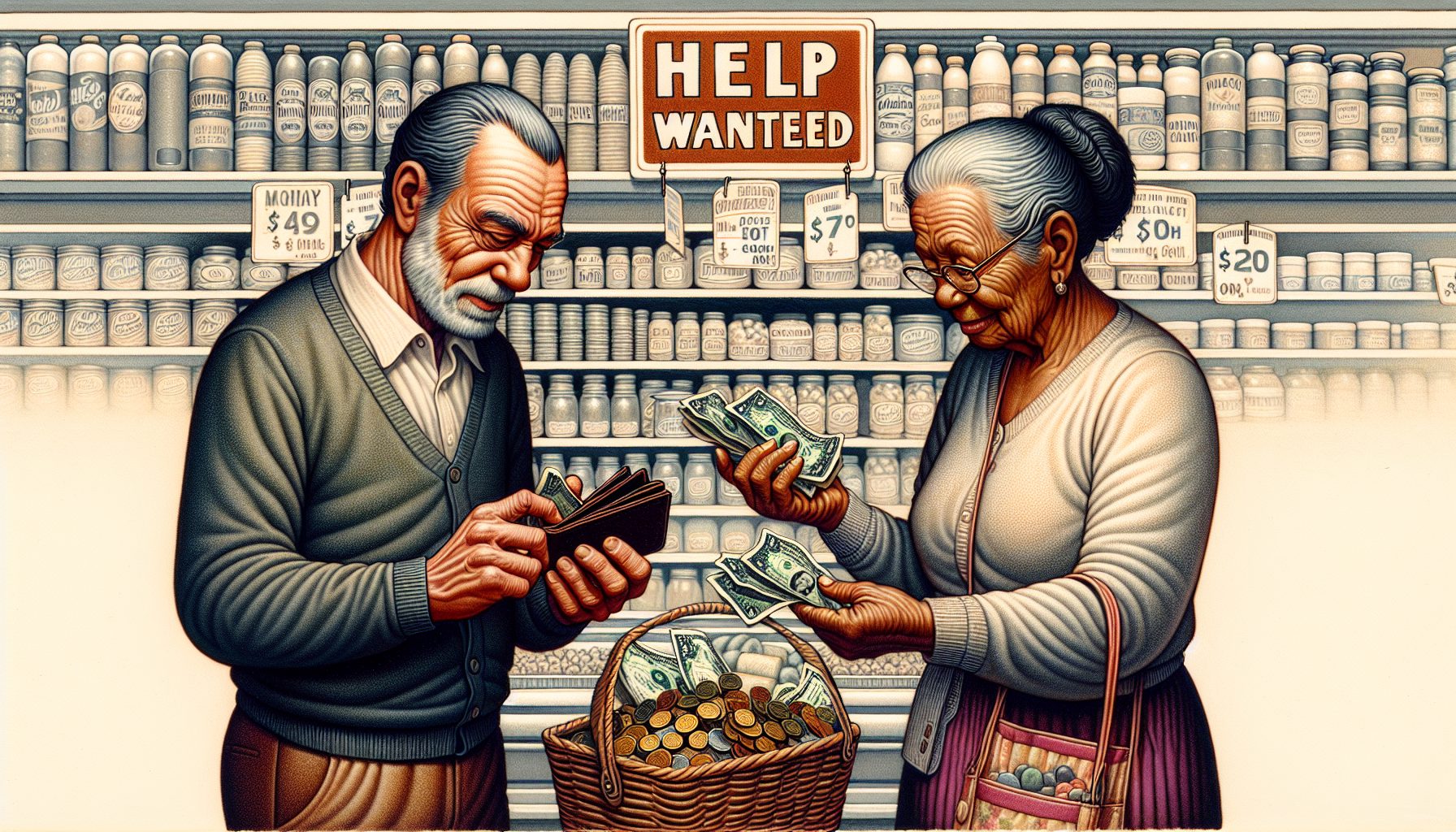

Almost every project is subject to delays and cost overruns brought about by minor factors—worker illness, supplier delays and the like. Slip happens.

KEY SKILL

Troubleshooting

The ability to spot problems early and resolve them quickly. Smart managers sometimes insert cost and schedule buffers to counter the impact of variation.

REAL-WORLD EXAMPLE

Project: Deployment of resource software in all divisions of multibillion-dollar company

What happened: In 1994, $5.7B apparel-maker VF Corp. embarked on a five-year plan to install SAP’s resource-planning software across the entire company (Baseline, Case 003, October 2001). It didn’t work out that way. The rollout to the first division took 15 months longer than expected when promised software modules didn’t materialize. More recently, VF abandoned a year-old effort to implement SAP at its second-biggest division, because that group lacked the resources to do the integration work.

Project team grade: B-

The steps VF took to address SAP’s limitations (such as doing some custom development) kept the initial deployment from falling even further behind schedule. But that experience should have kept VF from trying to deploy SAP at a division with fewer resources.

THE THREAT

Foreseen Uncertainty

Threats are major but easy to identify—like the multiple hurricanes in The Perfect Storm. The only question: Will it happen?

KEY SKILL

Contingency-planning

Is it true only the paranoid survive? It is with these projects. Best suited: those with the intuition to anticipate obstacles and the discipline to formulate alternate plans ahead of time.

REAL-WORLD EXAMPLE

Project: Wireless rollout

What happened: When transportation company J.B. Hunt decided in 1997 that it needed to do a better job of tracking the location of its trucks and trailers, the wireless industry was in its infancy (Baseline, Case 006, November/December 2001). The $2B company paid the price for being an early adopter—the three vendors it has used on this project have either gone out of business or restructured. As of last fall, Hunt had only 5,000 vehicles equipped for wireless, a mere third of its target for the time.

Project team grade: C-

Hunt had no Plan B—like subcontracting the development of its wireless system to a consultant that would have assumed the risk of vendor failures in an emerging market.

THE THREAT

Unforeseen Uncertainty

Many managers say it’s the risks they can’t see that worry them the most. Sometimes, a succession of moderate risks, each foreseeable on its own, crash down on you all at once.

KEY SKILL

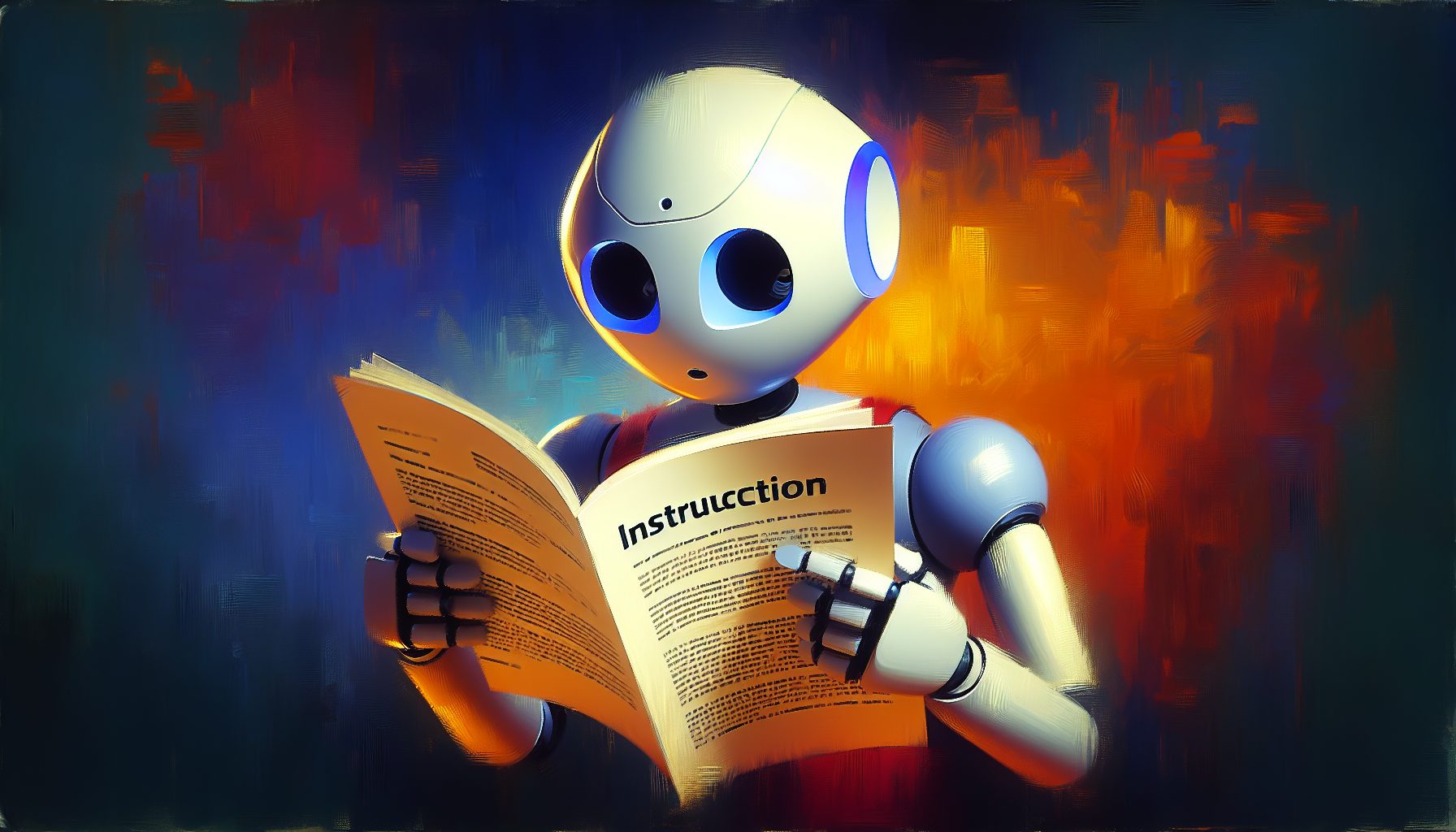

Relationship-building

When you’re dealing with gremlins, it helps to have friends—or at least relationships of trust with peers, managers and business partners. The shared dependencies that result give you resources to react to whatever comes.

REAL-WORLD EXAMPLE

Project: Tapping an outside consultant to manage a major systems transition

What happened: Collectibles-maker Department 56 was following a well-established tradition when it hired Arthur Andersen in 1996 to help upgrade its J.D. Edwards software package (Baseline, Case 014, March 2002). But using a consultant doesn’t mean you can take a vacation from your project. Not realizing that deploying ERP takes longer than advertised was Department 56’s first mistake. Its second was not entering 1999 price and inventory data into its old system, forcing it to cut over on the go-live date of Jan. 1, 1999, ready or not. The $200M company paid for its errors—for not staying on top of Andersen, in particular—with a screwed-up system that cost it millions in lost sales and bruised its image. It got $11 million out of Andersen in a lawsuit earlier this year—too little, too late.

Project team grade: F-

(Summer session for these guys.) It’s always a bad idea to put all your eggs in one basket—but if you do, you should take Mark Twain’s advice and “watch that basket.” Department 56 didn’t.

THE THREAT

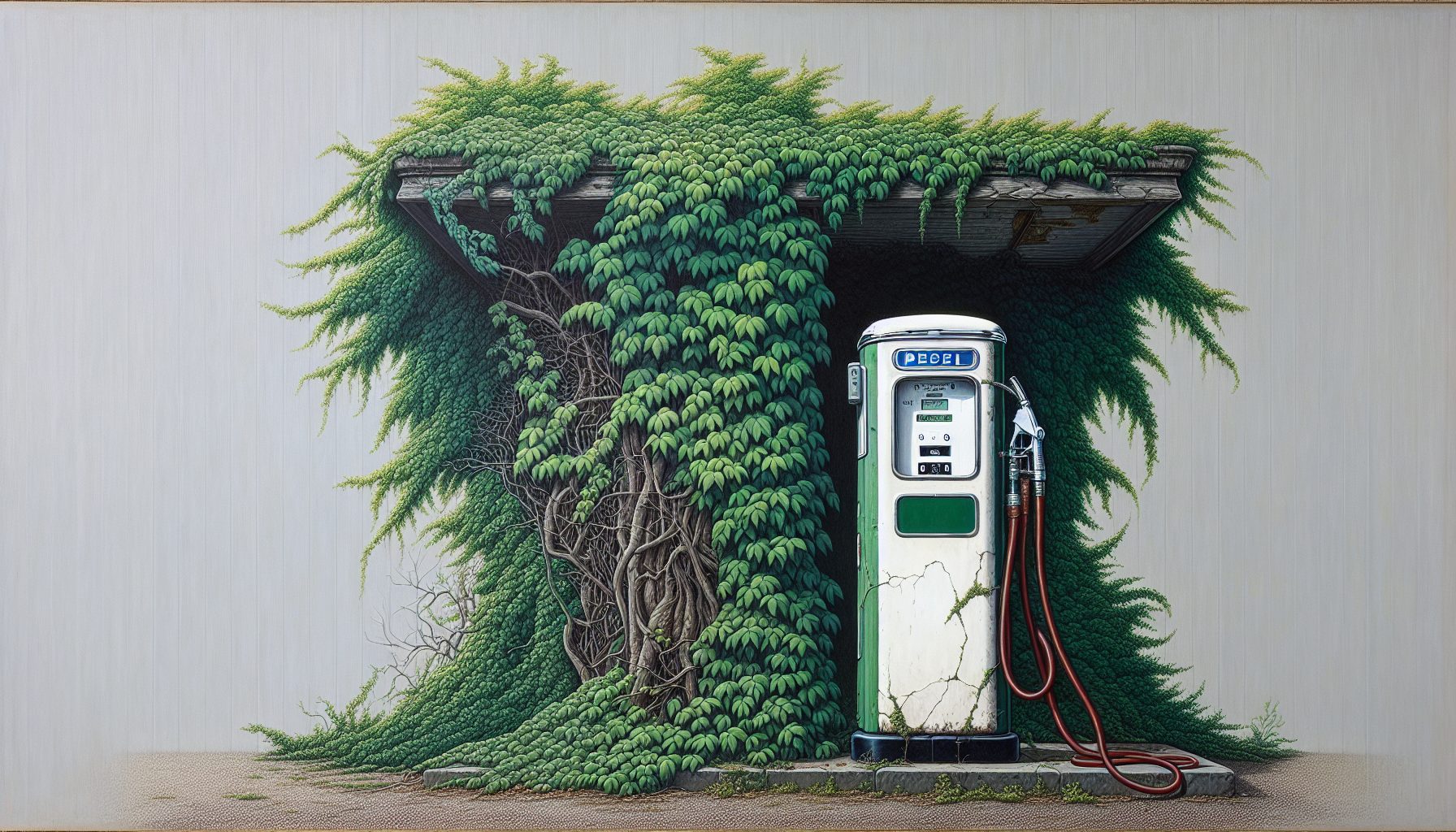

Chaos

Unforeseen events may invalidate goals, over and over. These projects often have no clear structure or definable endpoint.

KEY SKILL

Entrepreneurship

Sudden, dramatic changes in the dynamics of a situation call for improvisational skills. You learn rapidly and adapt—or you fail.

REAL-WORLD EXAMPLE

Project: Recovering data and applications under extreme time pressure

What happened: Despite the deaths of 180 of its technology workers in the Sept. 11 World Trade Center attack, trading firm eSpeed had its service up and running by the time the bond market reopened on Sept. 13 (Baseline, Case 002, October 2001).

Project team grade: A

Yes, the project team had disaster-recovery plans in place (it was prepared, in short, for a foreseen uncertainty). But no one could have predicted the scale of this disaster. The Cantor Fitzgerald subsidiary’s creativity—routing calls through its London office when domestic circuits were not available, for instance—was clearly entrepreneurial.