If you worked in Sigma-Aldrich’s customer service group three or four years ago, you performed some ugly gyrations to fill the orders of online shoppers.

Like a lot of companies, Sigma-Aldrich—a supplier of chemicals to research laboratories—put up an electronic- commerce site in late 1998. At the time, the company didn’t expect much. It hadn’t even connected the Web site to core inventory and order-processing systems. It was just an experiment to see what the Internet could do.

Turns out that lab-coated scientists searching for new weed killers, or perfumes, or potential cancer cures liked ordering their chemicals from Sigma’s site, dubbed Pipeline. Web orders arrived in unexpected volumes. Pipeline brought in $1 million in sales within six months of opening. That’s a lot of point and click, considering that a typical order is worth just $200 to $300.

Suddenly, Sigma had to run like mad. Not only did the company lack logical routines for managing Web sales, but the way the site was built—isolated from the SAP software that runs Sigma’s inventory, sales and distribution groups—actually bogged down sales.

The starter version of Pipeline was built on the IBM Lotus Domino Web server. That was mainly because Domino was the software in which Sigma, a $1.2 billion specialty chemicals maker, had created its product catalogs. Domino didn’t talk to the SAP enterprise resource planning applications, which Sigma had begun rolling out the year before.

To move a Web sale through Sigma, workers had to key incoming online orders into the SAP order-processing application manually, transcribing them from flat files spit out by Domino. Then, because the Web site didn’t have current inventory information, sales agents often had to phone Web customers to tell them of backlogs or changes to ship-dates.

A typical Web order took 1.5 times longer to process than a traditional phone order. So where it took about eight minutes to handle a phone sale, one from the Web ate up 12 minutes.

All told, customer service agents who averaged 60 telephone orders per day could do just 40 to 45 Web orders a day. That was bad news for Sigma, and the experience was bad for online customers, who were getting only the veneer of an electronic transaction.

“We created all these Web orders that were less efficient,” says Brad Johnson, director of e-business at Sigma in St. Louis. “It took us two months after deploying that first Web site to realize we needed to integrate with SAP.”

The realization was the easy part; making it happen was hard. Sigma runs SAP’s R/3 suite, version 3.0, with no Web support built in. Johnson had to find middleware that could translate the Web attributes of Domino into the language of SAP, and vice versa. He talked to 15 vendors before Haht Commerce, in Raleigh, N.C., came and did a demonstration of its middleware that convinced him to buy. Sigma also hired Haht consultants.

“They were able, in a couple of days, to show us they could integrate with that older SAP system,” Johnson says. “We had had problems finding people and technology for doing that integrating.”

The result: Domino hosted Sigma’s catalogs of specialty chemicals and online search capabilities and enabled customers to place an item in a shopping basket. Haht then kicked in to query SAP about inventory levels, distribution schedules and pricing. Ultimately, Sigma dropped Domino altogether for the Hahtsite package of electronic commerce software, a cleaner setup. “An order is routed directly into the SAP system, untouched by human hands,” Johnson says.

The integration project cost $1.9 million and took six months. Internal technology and operations personnel accounted for 57% of spending, consultants from Haht and other firms were 17%, software was 21% and hardware, 5%.

The work brought benefits worth $4.7 million over the last three years, according to an analysis late last year by Nucleus Research, a consultancy that helps companies figure return on investment in technology projects. Haht’s funding of Nucleus’ study raises questions about whether every aspect of it is complete. Nevertheless, it’s easy to see what drove the benefits at Sigma.

To start with, the number of calls ringing into the customer service center dropped. After integration, online shoppers could see—as they placed orders— current inventory levels and delivery timetables. Previously, those two areas had prompted numerous questions from customers. And because software took over every step in processing Web orders, Pipeline became far more efficient than telephone ordering. If Sigma didn’t have its Web site but was still taking in the same volume of sales as it does today, it would have had to hire 26 extra call-center agents by now, Johnson says.

Even more important than the efficiency is the steady climb in online sales sigma has seen. In the last quarter of 1999, Pipeline accounted for 5% of Sigma’s U.S. Sales of scientific research chemicals. Last quarter, it was up to 19%, or $31 million. Johnson says the site is on track to generate $140 million in sales this year. Once Pipeline reaches 25% of sales—Sigma’s goal by the end of next year—the site should be profitable, says Karen Gilsenan, an analyst at Merrill Lynch in New York. The web site “Is allowing them to keep current customers happy and reach new customers,” Gilsenan says. “It’s an important competitive advantage.”

By the end of this year, Sigma will have poured $25 million into Pipeline, an average of $5 million per year. Maintenance and support of the existing infrastructure takes about $4 million per year, with $1 million going to new features and projects, says Doug Wagner, e-business product manager at Sigma. The bulk of that is labor costs. Sixteen technology people currently work on the site full time.

When it started in 1999, the integration wasn’t seamless. Although Sigma was in a rush to move off Domino, which was buckling under the volume of transactions at Pipeline, Haht at the time had its own limitations—namely, it didn’t offer an application for handling product catalogs. So Sigma ended up hanging on to Domino for several more months, until Haht created catalog software.

Still, the biggest problem wasn’t technology; it was people, Johnson says. Before pipeline, and even for a while after it took off, the group responsible for creating product catalogs was separate from the order-processing department. But once the company started selling online, the two had to work together. While sigma was experimenting with new technologies, it also had to pry some employees out of their traditional work habits.

For example, when new products were added to Sigma’s catalogs, such as kits for measuring the weight of a particular kind of molecule, the technologists working on the Web site had to be told immediately.

Moreover, in the past, the person who oversaw the creation and printing of Sigma’s product catalogs controlled that entire process. That’s no longer the case. “The catalog has to work with the commerce system and the order-processing systems, which isn’t true of the printed catalog,” Johnson says. “This [Internet] media requires that we can’t operate in our functional silos,” he says. “I fight this every day.”

Roughly half of Sigma’s Web orders come through the password-protected Pipeline site. About 30% to 35% come through business-to-business marketplaces in which Sigma participates, such as ChemWeb. The remainder are generated through private online procurement applications customers set up directly with Sigma.

Now that Pipeline is stable, Sigma is working to persuade more high-volume customers to set up such private exchanges. That would make it easier to organize and tailor content for individual customers, many of which have worked out custom pricing arrangements with the company. Sigma generated $10 million in Web business that way last year.

Plus, customers who spend the time and money to set up private exchanges aren’t as likely to defect to Sigma’s rivals. If the customer can work out special pricing rewards, all the better. Yale University and the University of Michigan are two customers that work with Sigma through private Internet links.

At the University of Michigan, for example, academic researchers can order from a list of 7,146 Sigma chemicals at negotiated discounts as much as 59% off list prices. They also get free shipping on those products (and pay a 6% shipping charge for chemicals not on the list). The deal is expected to save the university $310,800 this year.

Next up for Pipeline is using Haht software to cross-sell electronically. If one product is out of stock, Pipeline might suggest a substitute. Or if the site sees that a customer is ordering one chemical that is known to always be used with a second chemical, a box could appear on screen with an offer on the second product. Sigma is piloting Haht’s software in this area, called Market, and expects to deploy it this year.

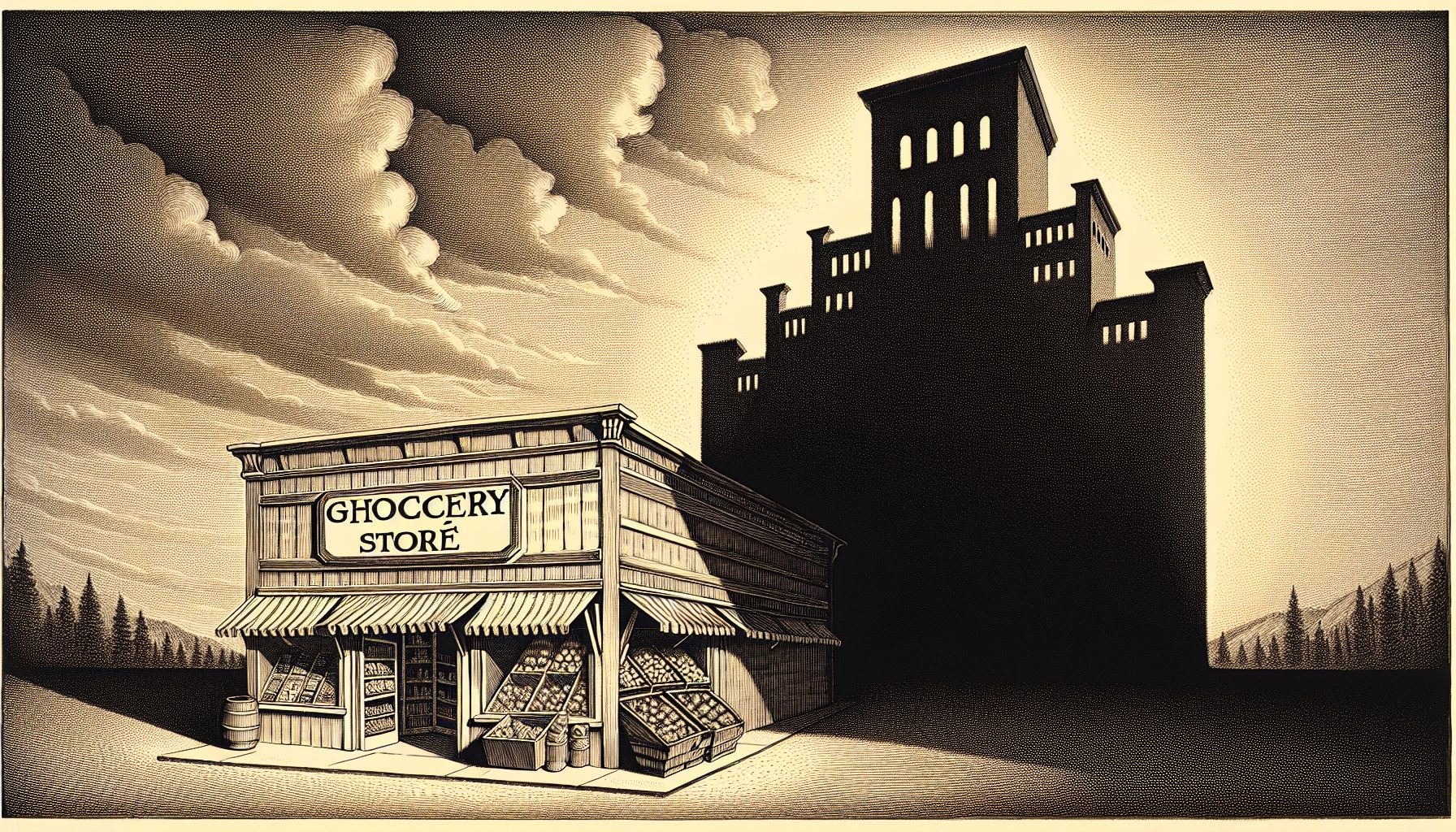

By no means do all, or even most, of Sigma’s 60,000 customers use its web site. For example, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, a $22 million biotechnology firm in Tarrytown, N.Y., wants the human touch for now. Scientists there researching treatments for obesity, vascular disease and other ailments buy small amounts of uncommon chemicals, often just a vial at a time.

Regeneron favors its traditional means of doing business with Sigma: over the telephone. Buying Sigma chemicals via the Internet is in the plans, but more so because Regeneron wants to move its procurement procedures online, than because of Sigma’s success on the Web.

Regeneron has built private online exchanges with two other suppliers so far, is working on a third and plans to do the same with Sigma in the first or second quarter of next year, says Sandy Peterson, Regeneron’s director of purchasing.

But there’s no rush. “There are times you need hand-holding and want to know that voice, and that they’re the authority on a raw material or compound you need,” Peterson says. Sigma is “a specialty company,” she notes. “With a company like that, you need personal relationships.”

Sigma, of course, knows many companies aren’t ready to start doing all their purchasing over the Internet. So while it likes to tout Pipeline’s success, the company has no plans to become an all-Internet entity. Indeed, the current goal of moving 25% of the company’s sales online by the end of 2003 is a sharp drop from the previous goal of 50% online sales. The idea now is to coax Web use where practical, but not to mandate the Web over more traditional channels such as the phone, fax or electronic data interchange.

“We don’t care,” says Johnson of the revenue source. “Doesn’t make any difference to us. If people are comfortable doing it a certain way, fine.”