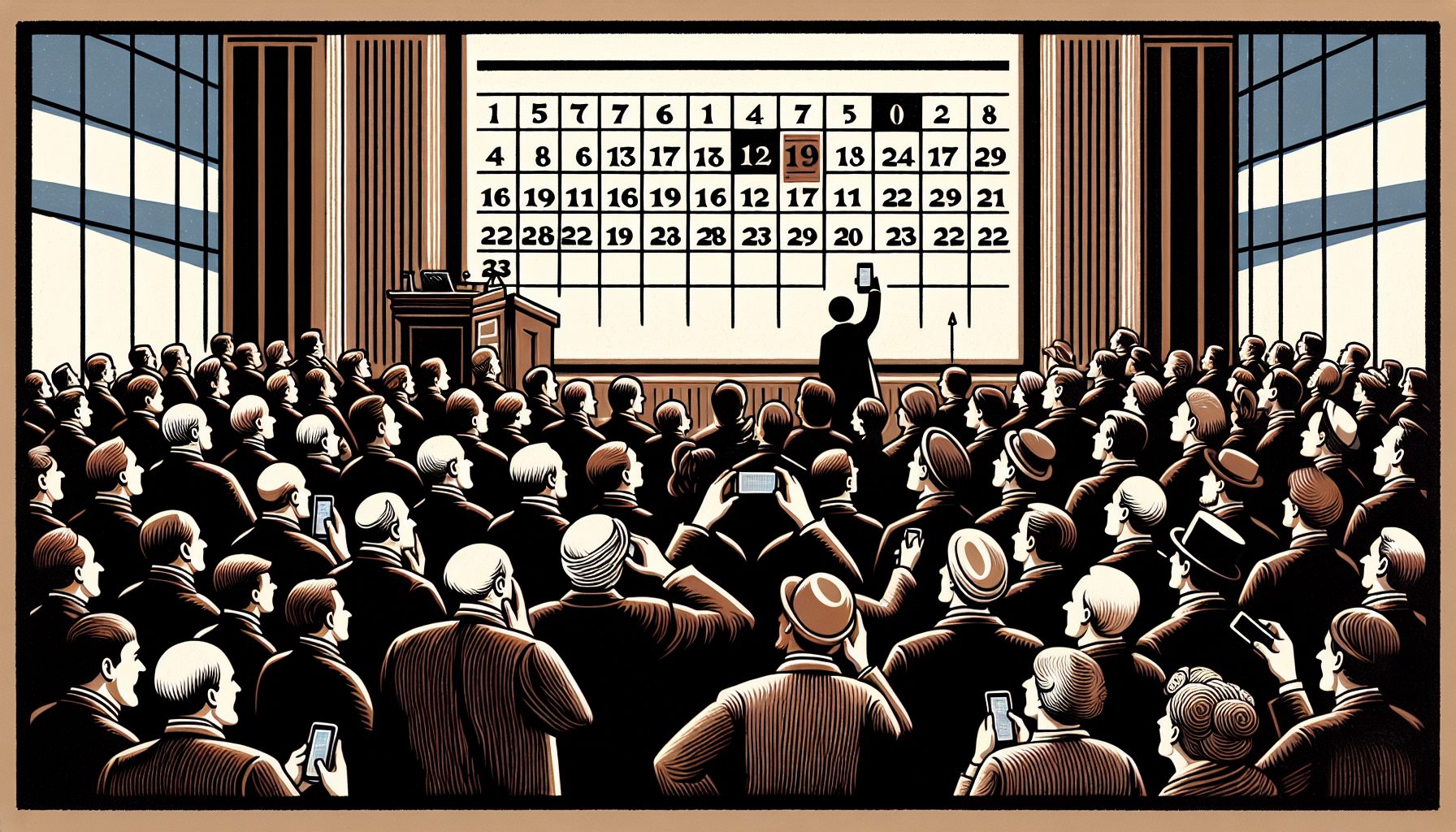

Carlos Gutierrez, secretary of the U.S. Department of Commerce, recently shared to a Congressional panel that the U.S. Census Bureau will drop plans to use handheld computers to help count Americans for the 2010 census, increasing the cost for the decennial process by as much as $3 billion.

The total cost of the 2010 census is expected to reach between $13.7 billion and $14.5 billion. The bureau had planned to use handheld devices from Harris Corp., but the switch fell behind because of scheduling and performance problems. Cost overruns helped derail the plan.

Technological advancements in census taking isn’t just a nice thing, but an imperative. It took seven years to complete the 1880 census, and by the time 1890 rolled around the population had swelled by 12 million. Something had to be done, and a statistician named Herman Hollerith did it. He invented a tabulating machine that could read punch cards and a device to rapidly punch the cards. The 1890 census was finished two years quicker, and many millions of dollars were saved. A company Hollerith launched to sell his inventions later evolved into IBM.

In short, the only way the federal government can take an efficient inventory of the citizenry is through the innovative use of technology.

Flash forward to 2008, and once again the Census Bureau is looking to innovative technology to streamline its work. This time a handheld electronic device to replace the paper its canvassers use when they call on those who don’t return their forms.

But technology is not the real problem. “This is a management problem. It’s an organizational problem,” Gutierrez told a Senate oversight committee.

Are you surprised?

Sen. Susan Collins (R-Maine), ranking member of the Committee on Homeland Security and Governmental Affairs, isn’t.

“This committee is unfortunately no stranger to tales of federal projects and contracts that have gone awry, often at a heavy cost in taxpayer funds,” she said. “Far too often, the results of these projects seem to follow a similar pattern.”

Collins listed the usual culprits: poorly defined initial requirements and an inability or unwillingness of management to control “requirements creep” or cost overruns.

Something larger than poor project management is at work, however — it is the failure of top management in the bureau to assess and mitigate the risks inherent in such a major project. The leadership seemed to have its head buried comfortably in the sand.

“It should be noted that the problems with this contract seemed apparent to everyone except the Census Bureau,” said Sen. Tom Coburn (D-Okla.).

In other words, the problem goes all the way to the top, as these things typically do.

Are you surprised?