Like a lot of technology companies, SAP’s stock has taken a hit. It’s fallen from $58 in July 2000 to $18 this year, a drop of 69%. The cumulative wealth of its shareholders has fallen from $63 billion at the end of 1999 to $24 billion.

But, unlike a lot of mirages and outright frauds of recent vintage, this is a company with substantive products, a huge market and endless prospects. Its customer: any organization with a complex business to manage. Its home base: Europe. The state of information systems: Still infantile.

Here’s a litmus test:

At the subway station at Piazza Barberini in Rome, you can’t get a ticket from a human being. But it’s almost impossible for first-timers to buy tickets from automated machines.

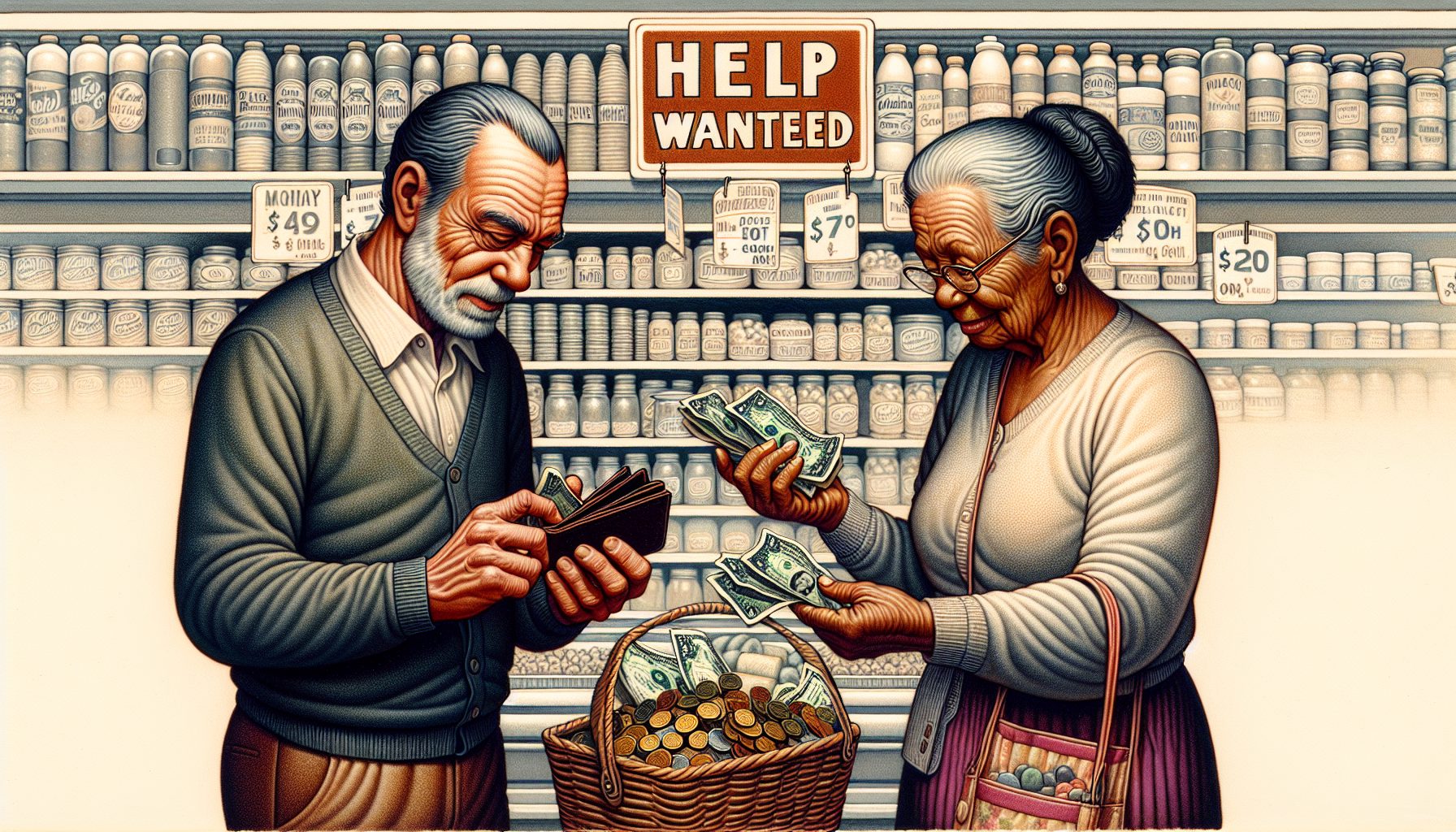

Change is capped at two Euro. So if you’re trying to buy 4 tickets at the equivalent of 77 cents each, the ten spot in your hand does you no good. You have to ascend to the surface and get a bank to break it into two fives.

Then, special notices printed out and taped onto the front of the machines inform you that change is given out in five-cent increments. You have to insert the correct change, down to the cent, to get the system to work at all.

So a five spot does no good either, when you want to pay for $3.08 of tickets. Thankfully, there’s a nice 18-column by 10-row chart that specifies what change you need to rustle up.

The real nuttiness of this “system” is that patrons wind up putting lots of one- and two-cent pieces into the machine. Yet the “system” cannot spit out any of those one and two-cent pieces in return.

Who thinks up these conveniences?

The moral is: As long as there are automated systems, there will be automated systems to fix, improve and fix again.

The transit authority in Rome is just one example of where SAP’s expertise is needed. Pharmaceutical giants haven’t gotten control of their manufacturing operations. Automobile companies are struggling to interact with suppliers. Retailers are baffled by the meaning of sales data. And many companies clearly need systems that don’t just automate existing processes, but can identify how to make processes more efficient.

Plunging profits and competitive pressures now demand this, unrelentingly. “We live in an era of constant anxiety,” says SAP co-chairman Henning Kagermann. “It will never go away.”

SAP made its mark helping companies figure out how to apply their resources to the effective production of goods or services. It is called enterprise resource planning.

Kagermann and fellow chairman Hasso Plattner now are bent on turning SAP into advisers to large companies. Kagermann wants SAP to serve CEOs who are “smart enough to do something with this information.” The result of applying SAP software, he says, is no longer “efficient production” but conduct of “intelligent business.”

But before suppliers of business intelligence software shake in their shoes, SAP will need to protect its own house. Microsoft now clearly has targeted SAP and is gearing up to be a major supplier of enterprise software.

SAP does not sound ready. Plattner says he takes Microsoft seriously. But at the company’s recent Sapphire users conference in Orlando, Plattner was asked how he felt about Microsoft being “at your throat.”

He fired back, “First of all, they’re not at our socks at the moment.”

It’s a flippancy he is likely to regret. Even if the two firms do not meet head-on for a few more years, that’s belittling the coming competition from Redmond. It’s the kind of quote football teams put on bulletin boards, just for inspiration.

And consider this: After 30 years in existence, the German software supplier, currently the giant in enterprise software, only pulls in $6.5 billion in revenue each year, before expenses.

By contrast, 27-year-old Microsoft generates $7.8 billion in annual profit. After all expenses.

If Steve Ballmer took it upon himself to play Nikita Khruschev, bang his shoe on desk and proclaim “we will bury you,” he would at least have the clear wherewithal to do it.