The quest to make computers easier to use has been going on for decades. Virtual assistants that respond to voice commands—including Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s Alexa and Microsoft’s Cortana—are among current efforts to simplify interaction with smartphones, tablets, computers and internet of things (IoT) devices. By enabling users to speak a command or request certain tasks to be accomplished, they eliminate the need to dig through layers of menu trees or squint at a small screen crowded with icons.

The latest entry in this field is Samsung’s digital assistant, called Bixby, which relies on artificial intelligence (AI) to improve human-machine interaction. An expert on speech recognition and language-based communication between humans and robots recently shared some insights on the subject with Baseline.

Typically, developers have “hand-crafted” intelligent agents to work with voice commands, a time-consuming process, observed Alex Rudnicky, research professor in the Language Technologies Institute at Carnegie Mellon University’s School of Computer Science. “Somebody had to figure out how each individual app would be activated by voice and what language the app would recognize,” he said, adding that the vast number of apps available makes it’s impossible to develop intelligent agents for all of them.

Translating natural language into something a system can recognize and act on is “non-trivial,” in his words. “You might tell your phone, ‘Find me an Italian restaurant in my neighborhood’ or ‘I’d like to eat Italian tonight,'” he offered as an example. “The system has to understand what you want and map the results into actions.”

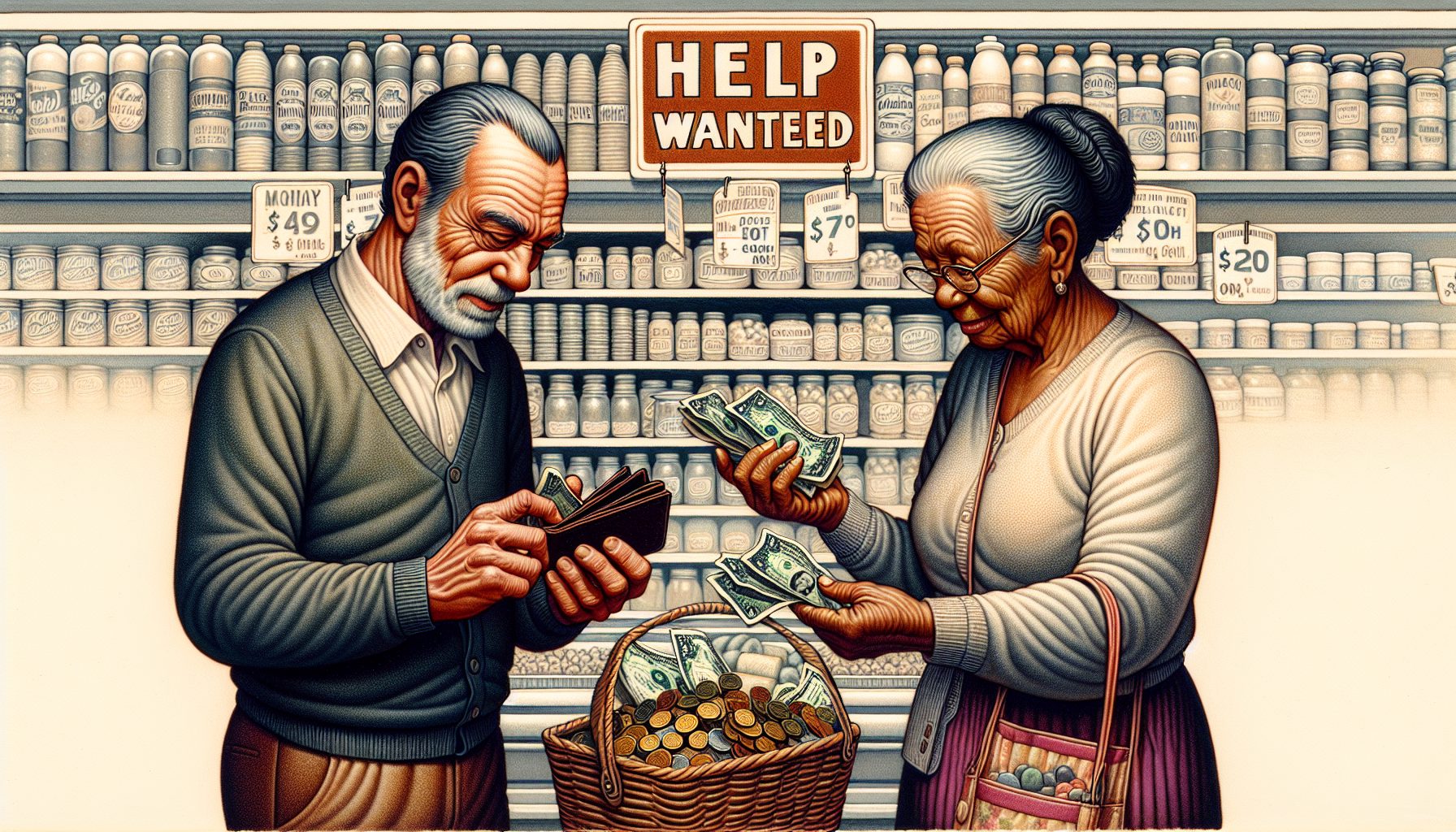

Difficult as it may be for a digital agent to respond to natural language, it’s a critical capability. “Humans are lazy,” Rudnicky observed. “Given the choice of something easy or something complicated, they will pick the easy option every time. So, if you give someone a choice between pecking away at a keyboard, poking at a screen or talking to a computer, they’ll choose to talk.”

The ability to speak to an app can eliminate or minimize the learning curve involved with conventional interfaces that require the user to learn how apps work. The “big payoff” will be making interaction with computers easier, he said.

“Say a corporation has sales people who need to understand their territory,” Rudnicky said. “They can sign on to a database, type in a SQL statement and get information, but that isn’t easy to do. It would be much simpler to say: ‘How many people aged 30 to 40, making $60,000 or more a year, have bought our widget in southern California?’ Developers are working on capabilities like this right now.”

This type of technology can also improve customer relationship management. “Chatbots, which used to be called dialog systems, are task-oriented,” he explained. “They can help users within the specific scope of a given site.

“But non-goal-oriented interactions tend to be more social, because people communicate on different levels. They don’t gruffly give just the required info; they also say hello and thank you. The goal is to create friendly chatbots that work more like humans, so they can leverage an interaction to create a better relationship with a customer.”

Eventually, voice will be integrated into such transactions. “People are built to talk to each other, not type at each other,” he said.

Feedback and Context

The industry has made recent strides in the right direction “to make agents smarter,” Rudnicky remarked. Some of the interesting ideas being explored in the research domain are now being translated into working products, including the Bixby.

Learning-based approach: This enables users to provide feedback to the system to improve performance, so an agent can learn and adapt to a particular user. In addition, this info can be sent back to developers, like a bug report, so they can figure out what works and what doesn’t, Rudnicky said.

Context awareness: This capability “considers what you say in a particular context, using multiple pieces of evidence to figure out what to do,” he explained. “People are really good at that, but machines aren’t.”

Cognitive tolerance: When a digital agent can recognize only specified wording, it’s a challenge for users to remember multiple commands. Samsung said Bixby will be smart enough to understand commands with incomplete information and execute the task to the best of its knowledge, and then will prompt users to provide more information and take the execution of the task in piecemeal.

Taken together, these capabilities can help a virtual assistant understand the semantics of an activity and accomplish a task without the intervention of developers—basically, creating a custom app that responds to user needs.

“Say you want your smartphone to help you plan an evening out,” Rudnicky suggests. “You use a few apps to do that. You might search for a restaurant, map the location, then message the information to friends.

“Imagine an agent that recognizes that you do the same things every Friday. It can help you manage the whole process and might even suggest that you try an Indian restaurant this time because you’ve eaten Chinese the past few weeks. It can act like a personal assistant.”