Popularized by the “small worlds” concepts of physicist-turned-sociologist Duncan Watts, social-network analysis (SNA) uses the theory and terminology of networks—nodes, links, paths—to show how people can work together more efficiently.

Think of a project team as a collection of nodes (people) and links (conversations, phone calls, e-mails). The most successful project teams have lots of links. Every player knows most of the others and information flows in many directions throughout the team.

But even a project team that shares information freely breaks down sometimes, especially reaching across departments, locations or levels of hierarchy, says Rob Cross, a professor at the University of Virginia’s McIntire School of Commerce and a research fellow at IBM.

It’s not necessary to do an exhaustive analysis to benefit from SNA. Most of its lessons are intuitive and straightforward:

- Don’t let yourself get overly central. A central position may help you feel important, but often slows the group. Designate an expert to make certain decisions, or create forums to solve problems and draw in peripheral players.

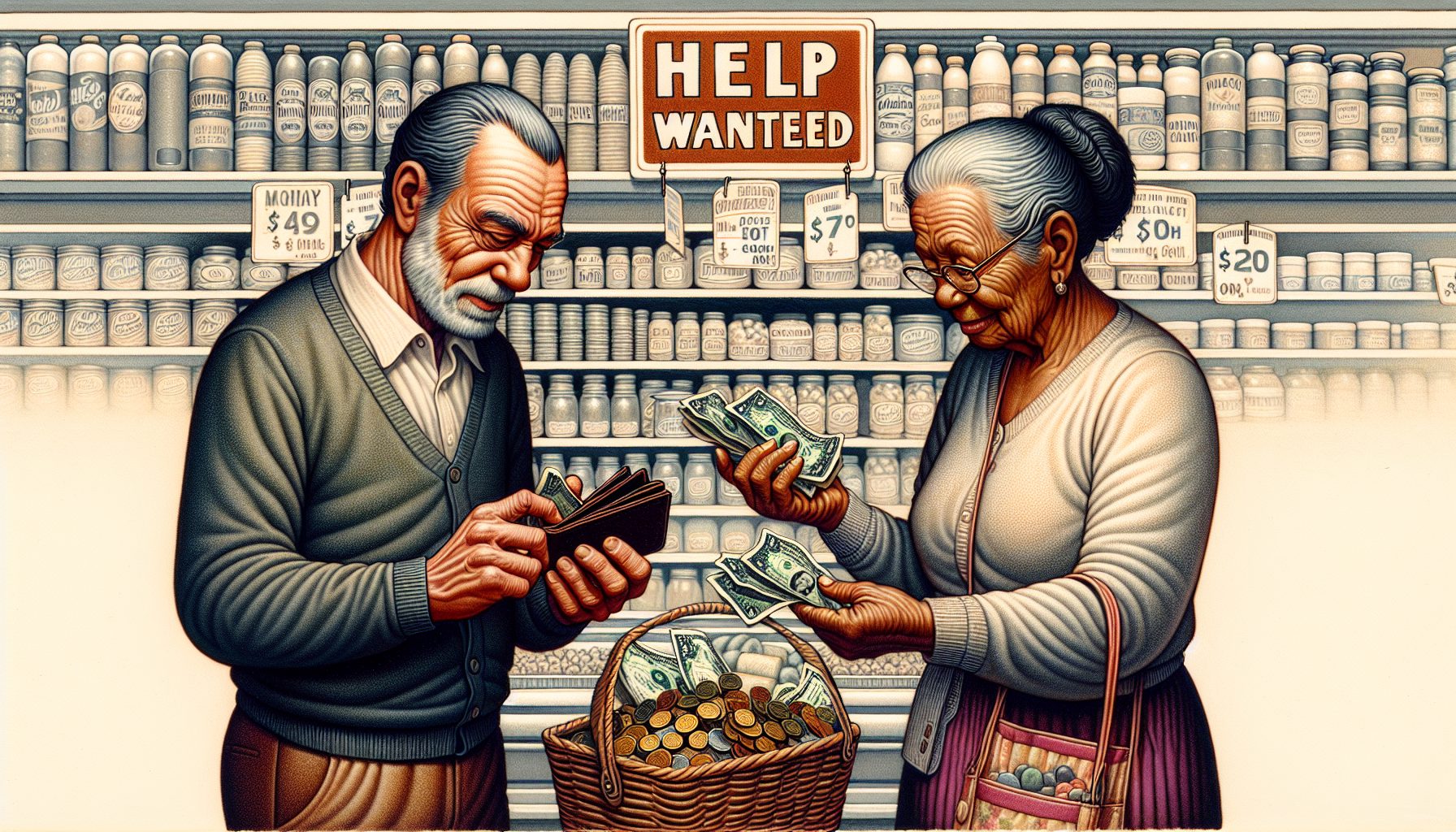

- Watch for overdependence on single links. The single-link problem occurs when one person holds critical information; is very good at his or her job; or simply won’t relinquish control.

- Reach outside yourself. People associate mainly with those who share their outlook and interests. Leaders need to resist this tendency because it tends to bias the information they receive and the actions they take.