“You’ve always got time for Tim Hortons,” is the familiar jingle that has enticed customers for years to the venerable Canadian coffee-and-donuts chain.

Time, though, is in short supply for Dan Dominick, Tim Hortons’ vice president of engineering services. At the moment, Dominick is juggling plans for 254 new store locations across Canada, and plans for another 220 retrofits—older Tim Hortons stores that are being renovated to more closely match the company’s latest model.

Then there’s the company’s invasion plans for the United States. Like a cold front sweeping down from Alberta, Tim Hortons plans to blanket the Northern states with up to 500 locations by 2008. That’s the coffee equivalent of a double-double (double cream, double sugar) piling up on Dominick’s desk. The new stores add to the 2,600 locations it already operates in Canada and 300 in the United States.

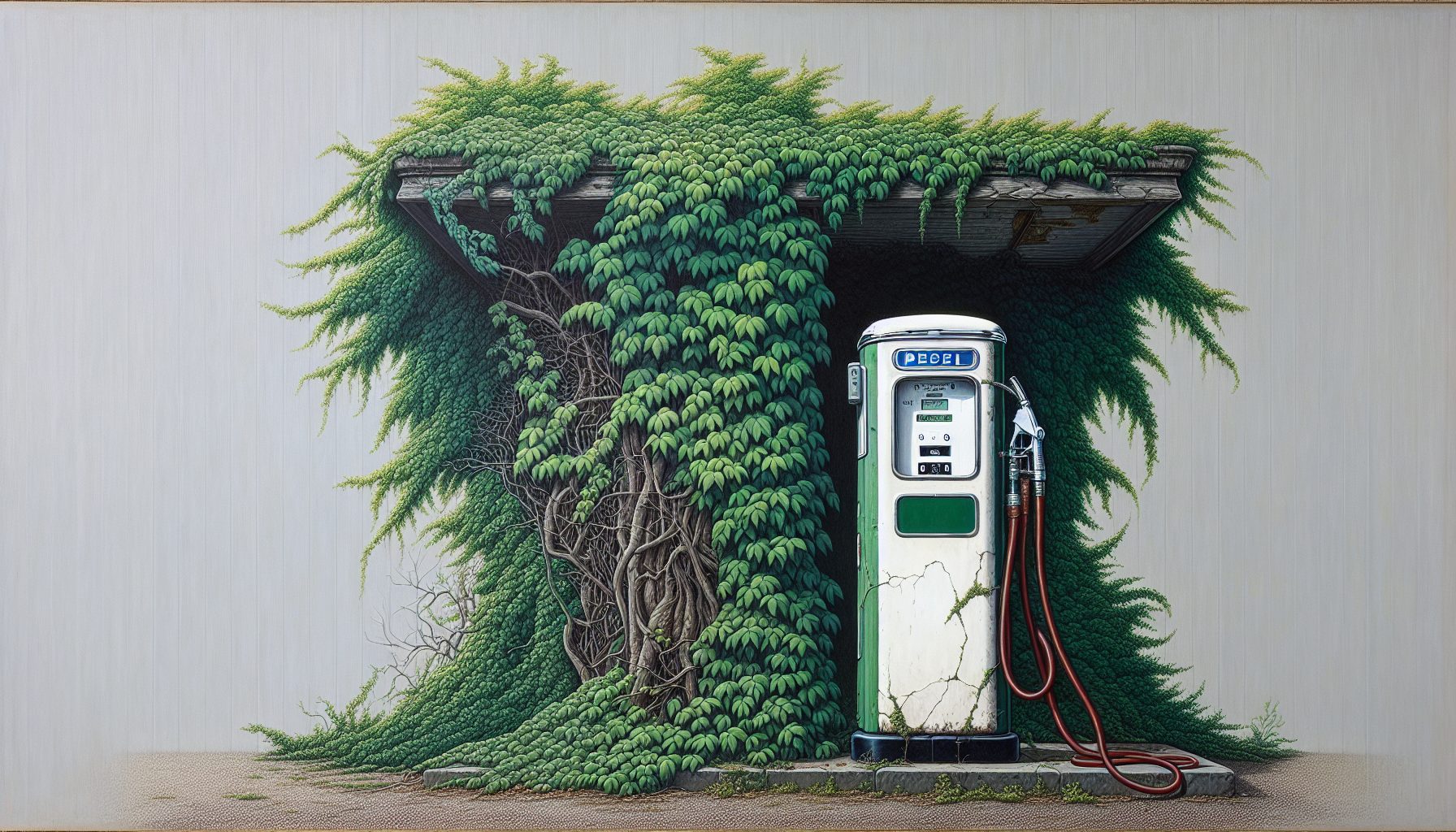

Until as recently as 2003, managing those projects was literally an exercise in shuffling huge volumes of paper. Looking to punctuate his point, Dominick gets up from his desk at the company’s headquarters in a suburban office park in Oakville, Ontario, and takes a quick stroll to a rather empty-looking corner of the building. “We had 916 filing cabinets with about 10 million documents,” he says. “In total, they were taking up about 3 million square feet of office space.”

But no more. Like a box of the company’s signature Timbits mini-donuts opened at a hockey rink, the filing cabinets are gone. Tim Hortons has completely reengineered the way it manages construction projects through the use of project management software, in this case a hosted version supplied by Expesite of Columbus, Ohio.

The Tim Hortons experience offers companies valuable lessons not only in the benefits that can be gained through the use of project management software, but also in the challenges and pitfalls involved during the deployment.

Dominick and his team found as they rolled out the software that construction cycles actually began to increase, rather than decrease, because of training issues. Outside contractors and service providers in particular struggled with learning to use the application. Tim Hortons also had a number of ideas on how to customize the software to make it more closely match its operations, but Dominick wasn’t prepared for the bill that went along with those specially designed features.

As the bumps were smoothed out, however, the project management software helped Tim Hortons shave about 30 days off its construction cycle. Just as important, it helped Dominick save close to $1 million in annual operating and administrative costs.

Tim Hortons is to Canada what Krispy Kreme is to North Carolina, or Dunkin’ Donuts is to Massachusetts. In fact, it’s as much a Canadian institution as toques, back bacon and hockey.

The chain is named after a popular defenseman who played with the Toronto Maple Leafs during the 1960s, helping them win four Stanley Cups, including the team’s last Cup in 1967. Ironically, the Canadian icon was bought in 1995 by Wendy’s International, the Dublin, Ohio-based operator of the Wendy’s fast-food chain.

But while Wendy’s has struggled to grow in recent years as consumers watched their fast-food intake, Tim Hortons has prospered. (Wendy’s is in the process of cashing in on Tim Hortons’ success by spinning it off as a standalone company.)

Wendy’s same-store sales fell by 3.7% in 2005, while Tim Hortons has managed to maintain consistent annual same-store sales growth over the last decade of close to 16%. Tim Hortons sales are less than one-third those of Wendy’s, about $1.4 billion in 2005 compared to $3.78 billion, but the chain accounted for more than half of Wendy’s operating profit.

Which is why Dominick and his department have been so busy. The pressure is on to keep the growth going in Canada, and to stick-handle into the big league and grab a piece of the much larger U.S. market.

Construction project management at Tim Hortons is a highly involved process, requiring input from a number of internal and external sources. It begins with the site selection review, where potential locations are evaluated for traffic flows, zoning requirements, area demographics and real estate values. Corporate real estate and legal teams are brought in to finalize site requirements and file necessary development permits; this is followed by building design and engineering. Construction plans are then tendered to contractors, and construction must be closely monitored to prevent delays or cost overruns. In the meantime, store fixtures, tables, chairs, shelves and cookers are ordered.

Finally, the new location is turned over to the operator—usually a franchisee, although Tim Hortons does operate corporate-owned stores.

Until 2003, when the project management software was put in place, it took an average of 390 days—more than a year—to go from finding the dirt for the new location to opening the doors on a new Tim Hortons. About 50% of the time, or six months, was tied up in going back and forth with city planning councils to gain approval for development permits. Dominick knew there was very little he could do to speed up that part of the process.

However, the remaining six months included finding a site for the new store, approving architectural plans and drawings, finalizing budgets and tendering construction contracts. That was the area he planned to attack.

It’s a complicated process whose backbone is built on communication, and when that communication is largely by phone, mail and fax, the potential for breakdowns is high.

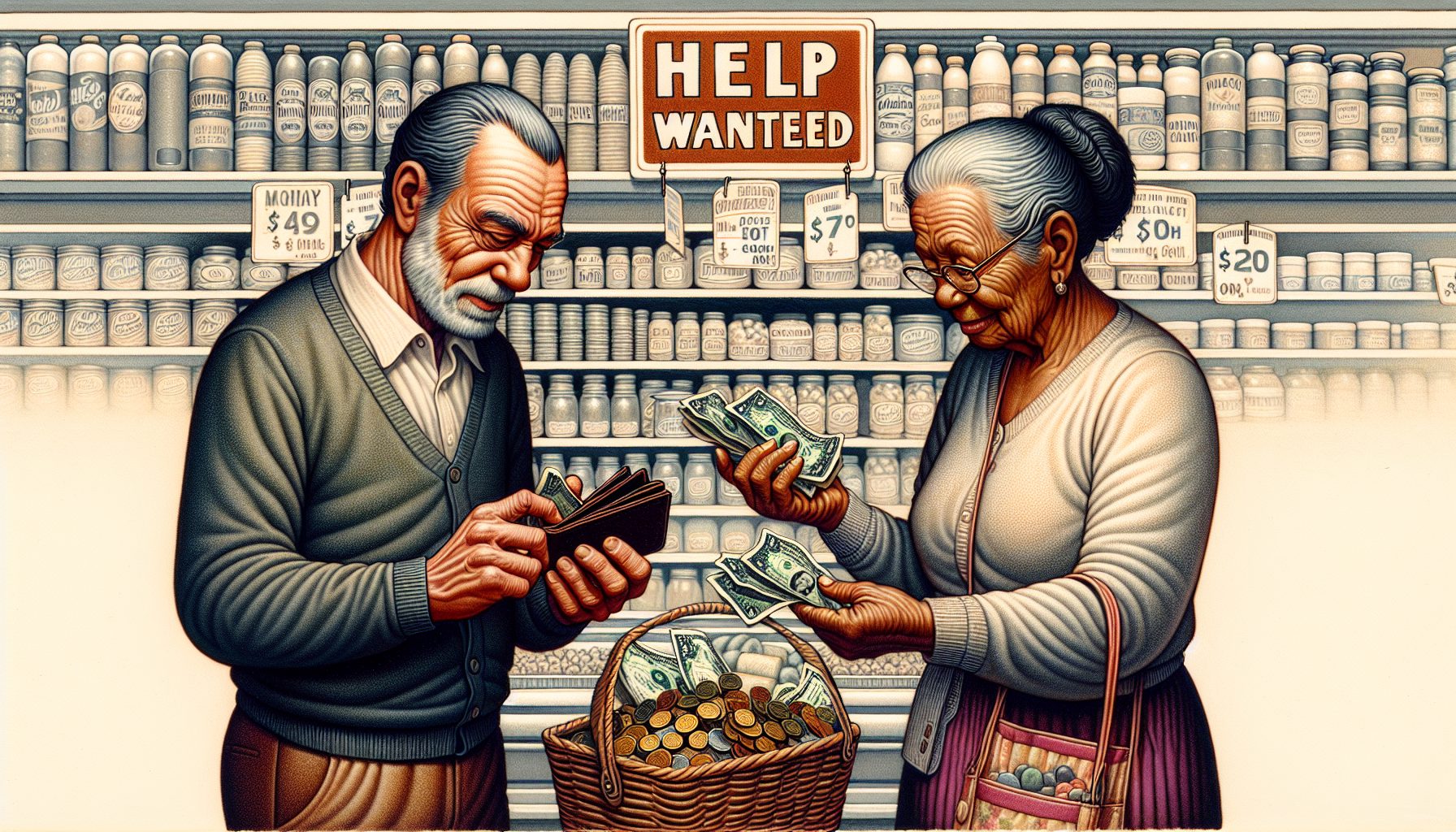

Bringing Tim Hortons into the modern world of project management was no cakewalk for Dominick and his development group, which has about 77 employees in Canada and another 20 in the United States. At various times, he approached senior management with the concept of digitizing the development cycle by making better use of the Internet, but the idea was quickly dismissed.

“As far as they were concerned, it was just going to cost money,” he says. “This company is run by a bunch of street-smart guys who like to hold a document in their hands. If I was going to get anywhere with it, I had to prove the business case first.”

Dominick built the business case by looking at one specific area of the development cycle—architectural plans and drawings. The company was spending about $250,000 a year alone on drawings that were printed off for contractors. Further costs such as fax, mail and courier services brought the bill up to $425,000. By making the drawings available online through a secure Internet project site, as well as other documents such as request for proposals and construction budgets, Dominick estimated savings could be close to $850,000 a year.

“Forget about time savings, which was the thing I was really after,” Dominick says. “I had to prove it to these guys in hard-dollar savings.”