Like small and agile drones, servers with Intel processors are eating into a realm once dominated by the proprietary (and expensive) queen bees of traditional Unix and mainframe systems.

The Public Broadcasting Service used to have a mélange of massive Unix servers powering its data center in Alexandria, Va. About five years ago, pbs decided to transfer all of its applications to servers running Intel processors.

What changed? André Mendes, pbs’ chief technology integration officer, couldn’t stomach paying for proprietary hardware anymore. “We felt the price/performance [ratio] of Intel platforms just could not be beat,” he says. Now the broadcaster uses Intel-based servers from Hewlett-Packard and ibm to handle almost all of its data needs, from Web serving to distributing video feeds to 349 stations.

Running high-performance applications on Intel servers—hardware that was originally designed for personal computers—used to be seen as risky, if not out of the question. Servers using processors found in PCs were written off as light-duty pickups compared with Unix or mainframe 18-wheelers.

It’s still true that individual Unix systems can handily speed past systems that use Intel processors. But per transaction, the Unix bunch also costs three times as much or more, based on a system’s price divided by its transaction rate, according to recent benchmark tests published by the independent Transaction Processing Performance Council. Today, Mendes is part of a growing group finding that fleets of multiple Intel-based servers working together are the less expensive and more flexible option.

Driving the sector’s economics are the millions of Intel-compatible processors (also known as “x86” chips after Intel’s old nomenclature) flowing into personal computers. In 2003, idc says 44.6 million PCs were sold worldwide, 4.7 million of which were servers. By contrast, 523,000 Unix servers with reduced instruction set computing (risc) chips shipped last year.

The sheer size of the Intel processor market has caused prices to drop as performance of the chips has steadily increased. Intel claims that a server with four 3-gigahertz Xeon processors (its fastest multiprocessor-capable chip today) performs 3 to 4.6 times faster, depending on the application, than a top-of-the-line system four years ago with four 700-megahertz Pentium IIIs. As faster chips roll out, prices for the previous generations typically fall; for example, Intel last month cut the price of its 3.6-GHz Pentium 4 by 35%.

As a result, worldwide sales of Intel-based servers have been booming— up 14%, to $5.1 billion, during the first three months of 2004 compared with a year earlier, according to idc. Meanwhile, the Unix server market was down 3%, to $4.1 billion, in the same period. Consider this telling change: Sun, which once insisted on selling only servers with its own microprocessors, now offers low-end servers with Intel-compatible processors from Advanced Micro Devices (amd) to compete with hp, ibm and Dell, the three powerhouse players in the segment.

Don’t count on Sun winning business from someone like Aaron Branham, vice president of global operations and networking at job-search company Monster Worldwide. In 2000, Monster acquired JobTrak, which ran a career site for college students and alumni. JobTrak, Branham found out, had been paying about $500,000 per year in leasing and maintenance fees to Sun for a Sun Fire 6800 server.

Most of Monster’s other online properties were already running on standard Dell servers with Windows. Branham’s team promptly ousted the Sun box and rewrote the applications for the JobTrak site (now called MonsterTrak) to run on eight Dell machines, a project that cost a total of $150,000. “We knew it was going to be much cheaper to go with Intel servers,” he says.

Plus, Intel servers let an organization add computing power more easily because they don’t require a colossal capital outlay, says Damien Bean, vice president of corporate systems at Hilton Hotels. Buying larger, more expensive Unix servers means “you have to take it up through the cfo to get it approved,” he says. “You can’t be as nimble.”

Another benefit: There’s less chance of getting locked in to one supplier. Chips are available from Intel and amd, and they can run a broad array of operating systems, from Linux to Windows. “It never really hurts to have two vendors in the server room,” says pbs’ Mendes.

But one downside of PC servers is that they can become problematic to manage in large numbers. After all, it’s potentially a bigger task to care for and feed 100 individual servers than one gigantic system. The key, say users of Intel-based servers, is to rigidly standardize on a set of server configurations so that machines behave the same way and use the same replacement parts. “We’ve developed all the tools and procedures to manage hundreds of servers,” says Monster’s Branham.

Another catch is that Intel-based servers are not quite as reliable as proprietary systems. That’s because Intel servers include components from multiple suppliers, each independently engineered and manufactured, says Jay Bretzmann, ibm’s director of server product marketing. He says none of the x86 servers on the market, including ibm’s, can achieve 99.999% uptime—a standard measure of high-reliability systems—without extra measures, such as having a standby server ready to kick in if the main one dies. “The hardware is not a ‘five-nines’ platform by itself,” Bretzmann says.

One way the industry is addressing those management and reliability questions is with “blade” servers. These pool resources such as power, cooling, storage and network connectivity for multiple server “cards” that run processors and memory. The idea is to save space and provide a more manageable alternative to dozens of standalone PC boxes.

So, it seems, everything old is new again, as blade servers start resembling mainframes. “From an operational standpoint, a blade system looks like a single box,” says Robert Wiseman, chief technology officer of Cendant Travel Distribution Services. And because the blades are relatively cheap, it’s feasible to plug in extra blades to boost the performance and availability of an application, he says.

“The chance you’d lose two blades at the same time is very small,” Wiseman says, “and the odds you’d lose three—well, that’s astronomical.”

Group Dynamics: Built to Serve

Category: Servers with Intel (or compatible) processors.

What It Is: Computer systems designed for network-based applications, typically running either Microsoft Windows or Linux operating systems.

Key Players: Dell, Fujitsu Siemens Computers, Hewlett-Packard, IBM, NEC, Unisys

Market Size: $19.1 billion worldwide, 2003 (IDC)

What’s Happening: New “blade” server systems can consolidate multiple physical servers into one unit by sharing power, networking and other resources. Also hot: server virtualization software, which lets multiple operating systems run on the same processor.

Expertise Online: The server section on IT Manager’s Journal (www.itmanagersjournal.com/servers) offers user-posted articles, discussions and links to news stories.

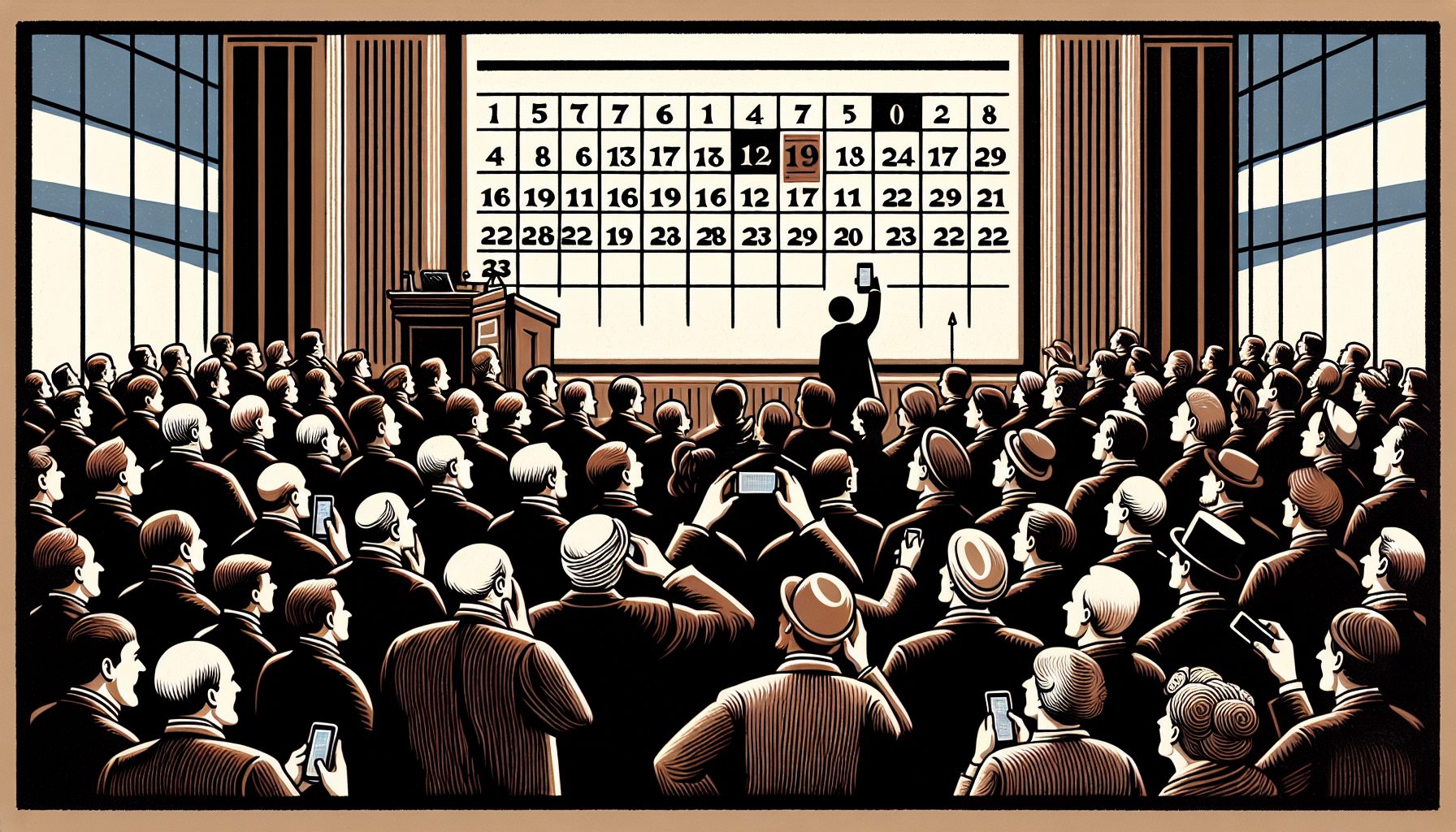

Worldwide Server Share

HP 32.7%

Dell 21.8%

IBM 17.7%

Fujitsu Siemens 2.9%

NEC 2.8%

Others 22.0%

For x86-based servers in 2003, by revenue*

*Total does not add up to 100% because of rounding

Source: IDC