NEW YORK (Reuters) – A drop in factory overtime hours to the lowest level since 2002 does not bode well for the manufacturing sector and has led many to expect widespread job cuts and a recession-plagued economy.

A decline in overtime, indicated by both government and private-sector data this month, coupled with falling factory use rates, means employers are taking more aggressive steps to cut production and rein in costs.

It is also a leading indicator of broader demand for workers, since employers initially make cuts where they have the most flexibility, by reducing variable rather than fixed costs. With unemployment at a two-year high of 5.0 percent, current trends may mean a higher jobless rate in 2008.

“Manufacturers invest a lot of money in worker training, so the first stage if you’re going to react to slower demand is to cut back on the hours worked,” said David Heuther, chief economist of the National Association of Manufacturers (NAM) in Washington, D.C.

U.S. manufacturing workers put in an average of 3.9 hours a week of overtime last month, down about 5 percent from 4.1 hours in the previous month, and 4.2 hours in the first two quarters of the year, according to government data.

By comparison, they averaged 4.6 hours a week in the fourth quarter of 2005 when the economy was in better shape, and 3.8 hours in the fourth quarter of 2001, near the end of the most recent U.S. recession.

For the total labor market, overtime hours were down 10 percent in 2007 from the year before, according to staffing services company Manpower Inc.

EMPLOYERS’ OPTIONS

Employers have multiple options to address falling demand for their products.

Cuts in overtime are a first step, followed by reductions in temporary and part-time staff, then eventually cuts among full-time staff. Companies can also cut payrolls without announcing layoffs by not replacing workers who retire, a frequent occurrence in factories.

Reducing variable costs may help an employer weather a short-term downturn, providing flexibility to quickly ramp up when demand picks up. But if the downturn proves lengthy, managers will need other options.

“If the manufacturing sector keeps going flat or down, then we’ll definitely see some labor cuts,” said Pete Ronza, a compensation and benefits expert at the University of St. Thomas in Minnesota.

Overtime reductions have proven to be a leading indicator, said Dan Meckstroth, chief economist of the Manufacturers Alliance/MAPI. Overtime rates fell before the 2001 recession and picked up in advance of a manufacturing recovery in 2003.

“(Overtime) is like inventory, it’s a buffer,” Meckstroth said.

The next few weeks are likely to show falling output, reflecting weak automotive and housing markets. A closely watched index by the Institute for Supply Management this month indicated contraction in the manufacturing sector. December industrial production data due on Wednesday are expected to show a decline in output and factory use rates.

If industrial production falls in coming months, job cuts will accelerate this year, with about 375,000 manufacturing jobs lost, Meckstroth said.

Last year, U.S. manufacturing employment declined by about 212,000 to about 13.9 million workers, even as industrial production and the overall economy were growing.

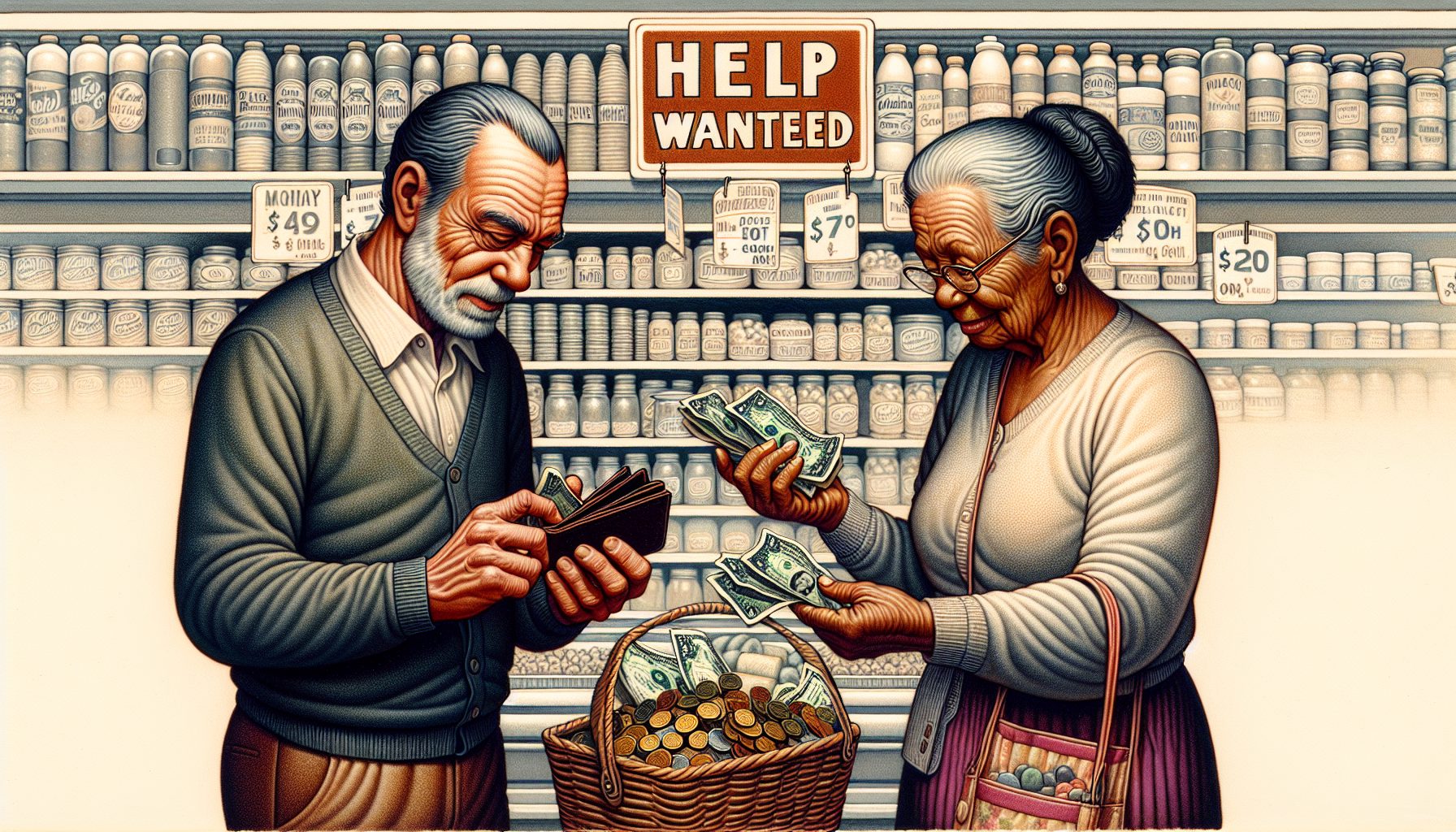

For workers who have grown accustomed to overtime, less overtime may mean having to make painful adjustments.

“If you really work a lot of OT, paycheck after paycheck, most people start counting on that money,” said compensation expert Ronza. “When you start cutting back, employees get angry because in essence they think they’re getting a pay cut.”

(Reporting by Nick Zieminski; Editing by Brian Moss)

Copyright Reuters 2007. All rights reserved. Users may download and print extracts of content from this website for their own personal and non-commercial use only. Republication or redistribution of Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Reuters. Reuters and the Reuters sphere logo are registered trademarks or trademarks of the Reuters group of companies around the world.