In October, Cathy Uhl gave a blood sample as part of a routine physical examination, but less than two months later—according to the hospital that processed her laboratory results—she was dead.

“You could say I was a little surprised,” Uhl says. “I was pretty sure I wasn’t dead, but you never know. The hospital explained it was just a computer glitch, but I’m still waiting to see what this is going to mean for me.”

It turns out St. Mary’s Mercy had recently completed an upgrade of its patient-management software system. (

Worse, that errant data wasn’t sent just to the shocked patients but to their insurance companies as well as the local Social Security office, which helps determine whether elderly or disabled patients are eligible for Medicare. Obviously, once a patient is dead, Medicare—assuming its electronic-records system is accurate—isn’t going to make any payments on bills for future medical services or medication.

St. Mary’s Mercy officials—some of whom also were misidentified as “expired”—scrambled to set up a hotline for affected patients, notified insurance companies and government agencies about the mistake and then went about fixing the code issue that caused the misidentification in the first place.

Whether or not the coding problem has been fixed—or how it was fixed—is not clear.

“To us, this is really not a very big story. We’re not going to elaborate any more,” says Jennifer Cammenga, a St. Mary’s Mercy spokeswoman. “It was a mapping error. That’s all we have to say about it.”

The hospital, in a statement, did say that it was “diligently working” with all parties involved and that it would likely take “several months” to resolve all the billing and insurance issues created by mistakenly identifying discharged patients as dead ones. The medical institution says that roughly 2,800 of the patients affected were Medicare patients.

“The hospital gave us a letter and told us to hold on to it in case the government or insurance companies have any questions in the future,” Uhl says. “Basically, all it has amounted to so far is a pretty funny story to tell and a small annoyance.”

Other patients haven’t been so lucky.

A landmark 1999 report commissioned by the National Academy of Sciences’ Institute of Medicine claimed that between 44,000 and 98,000 people die each year because of mistakes made by medical professionals, hospitals and other health care organizations. And even if the vast majority of mistakes are not fatal, service providers are still making disastrous errors in patient records—and treatment—despite the billions they’ve invested in information technology systems.

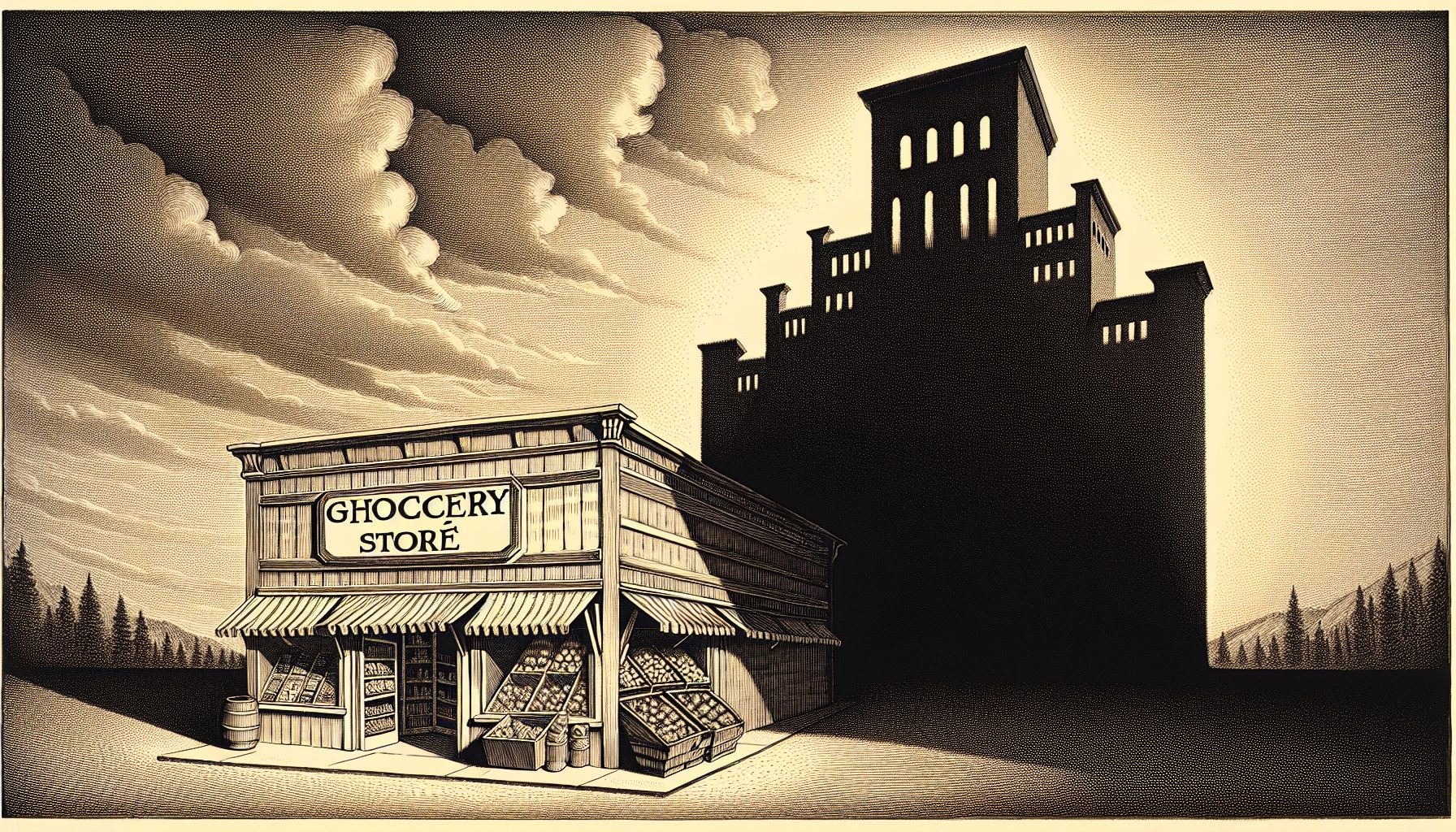

“Health care organizations have earned reputations as laggards in I.T. adoption,” says Jim Klein, an analyst at Gartner Inc. “Although there are notable exceptions, generally the reputation is well deserved. Productivity improvements in the U.S. health care industry have not kept up with the rest of U.S. industries.”

For instance, on Jan. 20, United Hospital of St. Paul, Minn., admitted to a laboratory mix-up that led doctors to perform a double mastectomy on a 46-year-old woman they mistakenly diagnosed with an aggressive form of cancer.

Linda McDougal was diagnosed with cancer in May 2002 and told that her cancer was so aggressive that a double mastectomy, chemotherapy and radiation were her only chances for survival.

Two days after her surgery, her doctor broke the news that no malignant tumors were found in the amputated breast tissue and, apparently, tissue used from McDougal’s biopsy was switched with tissue from another woman. That woman was eventually contacted and treated.