Bill Wimbish, 53, hasn’t had a full-time staff job in his field of managing telecommunications equipment since 2000, when he left Winstar Communications in Herndon, Va. He says it’s because of his age.

Last month, Wimbish drove seven hours from Homosassa, Fla., to Atlanta for an interview at a telecom company. “I signed in at the desk, and as soon as they came out to get me, their faces fell,” he says. “No matter [how] you present yourself, all they see is, ‘He’s older.'” Thinking that he’s not getting hired because of his age makes Wimbish mad: “It’s next to impossible to prove, but it’s very real and very palpable.”

In May, I wrote about how some companies are girding for the retirement of baby boomers, a generation that accounts for 25% of the U.S. population. As the oldest boomers turn 60 next year, FirstEnergy, Dow Chemical and others plan to match retiring talent with newcomers, to capture institutional know-how.

Bravo for thinking ahead, right?

Nonsense, Wimbish and other readers wrote to me in response. The urgent problem isn’t companies facing boomer exits, they said; it’s people age 50 and up who have to worry about getting the bum’s rush from employers.

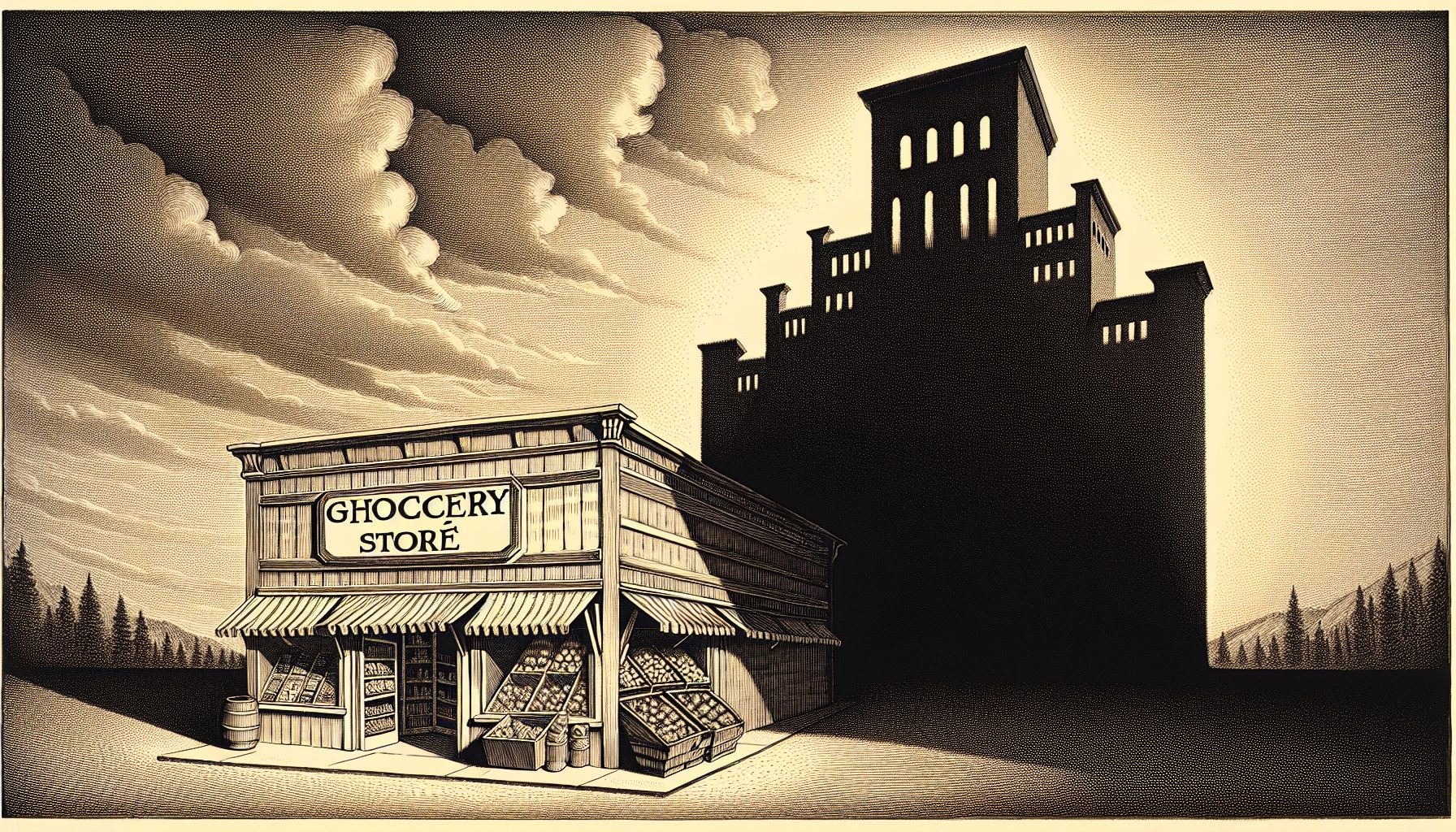

But mothballing these older workers is shortsighted.

As companies struggle to align technology with business goals, they’re taking a step backward by letting go seasoned staff who not only understand how to deploy systems, but, because of their positions and experience, grasp business and markets. The project manager who delivered software to calculate customer profitability for that growling VP in the home mortgage department will know better how to approach other projects with that same guy than would a newcomer.

Frustration abounds. John Filicetti, who is now a project management consultant at Ascentium Corp. in Bellevue, Wash., got laid off three times in four years, starting in 2001. “It’s been,” notes the 53-year-old, “a rough patch.”

Jim Lyons, a network administrator at Aon Corp. for five years, says he lost his job when Aon outsourced network maintenance and other tasks to Computer Sciences Corp. last summer. Lyons, then 51, spent 28 weeks looking. In March, he started as a technology administrator at New York University Medical Center.

Steve Cohen, 52, was a project manager at Acxiom Corp., which sells demographic data. Cohen, with computer science and M.B.A. degrees, was laid off in June 2001. He says he felt aged and priced out of the market. “Business has already started the boomer outflow by letting them go and replacing them with cheaper, inexperienced young people,” he wrote. “Retirement? Yeah, right.”

Cohen said he would get calls from companies asking why someone with his experience had applied for a mid- or entry-level job, and what pay he wanted. “These people were just filtering candidates … for keywords and salary ranges,” Cohen said. “I question whether I will ever get up to the level I was at. The paradigm has shifted.” He didn’t get another I.T. job for 2 1/2 years.

Cohen’s right—things have shifted. As dot-com companies disintegrated, good people lost jobs and executives cut costs. Who hasn’t read irritating memos about “working smarter” or “doing more with less”?

Now, some companies are hiring, with 16% of 1,400 CIOs polled by recruiter Robert Half International saying they plan to add staff this quarter. But age seems to play a part in why older workers struggle to find jobs. Last year, according to the U.S. Department of Labor, the average duration of unemployment lasted about 20 weeks. For men age 45 to 54, it lasted 25 weeks. But for men 25 to 34, it dropped to 19 weeks.

No ethical, law-abiding company discriminates by age. But perhaps some companies hesitate to hire older workers because they fear these people will be expensive short-timers looking to fill a few years before retiring.

But no one I’ve talked with who’s out of work thinks that way. Though a stint of five years in I.T. is considered long, Wimbish, Cohen and the rest say they would love to contribute at challenging jobs for double or triple that length of time. They bring depth and stability with their skills.

Companies that seek out younger, cheaper workers should watch out. They may end up doing less with less.