“Everything depends on I.T.,” says Robert D. Galey, chief information officer of Amtrak, the national passenger railroad system.

But not everyone.

Amtrak’s president, David Gunn, does not.

The 67-year-old Gunn, who came to Amtrak after heading up the New York City Transit agency and the Toronto Transit Commission, does not use digital technology. Gunn doesn’t send or receive electronic mail, Galey says. Gunn doesn’t even have a computer in his office.

That makes it critical for Galey to explain clearly what a new technology initiative is and why it is justified.

But Gunn did not come to Amtrak to save the train operator, bit by bit. He came to restore financial credibility—and get more Americans to ride the rails.

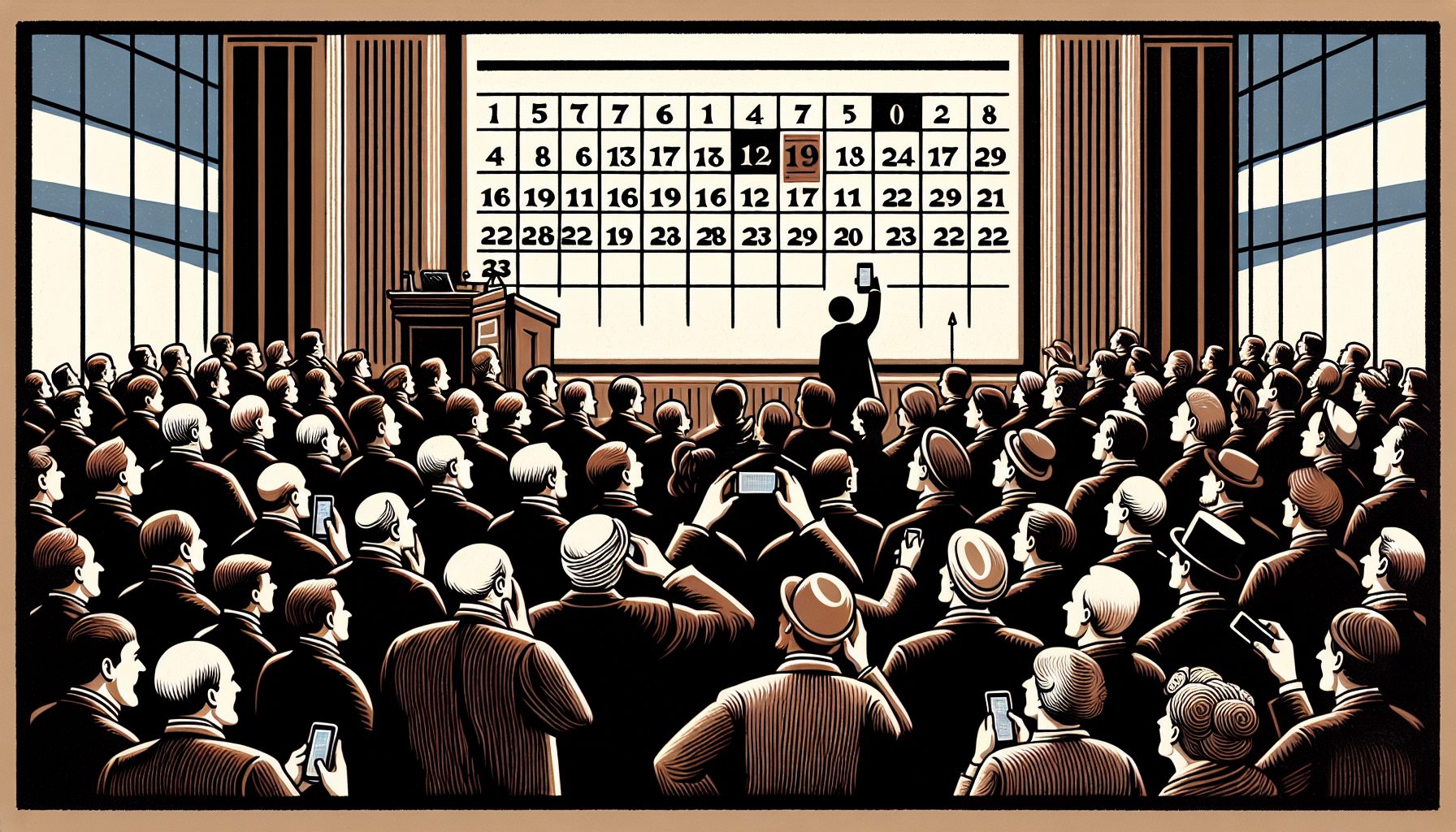

On one score, he is starting to succeed after two years at the controls. In 2003, Amtrak carried 24 million passengers, a 2.7% gain from 23.4 million in 2002. Not much? Since 1971, the ill-fated carrier has added only 3 million passengers to its yearly average.

Gunn has brought in new riders by essentially pursuing a faith-based rehabilitation of the railroad. “He has a Field of Dreams strategy: If we fix it, they will ride,” Galey told a gathering of corporate technology officers in December at New York’s Intercontinental Barclay Hotel.

That has meant pouring money into revitalizing the rails, rather than promising Congress that the system somehow would pay its own way. Gunn’s predecessor, George Warrington, had lost credibility by pledging to make Amtrak live within its means and take itself off life support from federal operating subsidies.

Gunn called that hogwash from the start. Peering at a perennial billion-dollar subsidy, Gunn asked for more. He said it would take consistent investments of $1.8 billion a year or so to improve rickety rails and replace doddering train cars—and make the Amtrak experience worthwhile for more people.

In Gunn’s two years as Amtrak’s head conductor, his tack has barely made a dent in the railroad’s long history of financial woe. Revenue in 2003 actually fell to $2.1 billion, from $2.2 billion the year before. Why? Amtrak used promotions to generate the record ridership—resulting in less revenue per passenger.

Its loss from operations reached $1.1 billion, up from $995.4 million. Adding interest paid on its debt, the net loss reached $1.3 billion from $1.1 billion.

The woe reached its zenith in summer of 2002, when Amtrak came close to not making payroll with two months to go in its fiscal year. The near-death experience meant a re-examination of how all parts of the railroad operate—and a newfound zeal for cutting costs.

For Francis Murphy, the line’s director of procurement, that meant converting Amtrak’s internal travel booking to an online, self-service system, delivered through Worldspan, a reservation operation used by large companies as well as Web-based consumer services such as Orbitz, Expedia and Priceline.

The goal: Eliminate 50% of all controllable travel expenses, Murphy says. Amtrak at the time was spending about $2.5 million a year on travel by managers and $4.5 million on travel by its union members, plus $4.8 billion on getting passengers delayed or otherwise inconvenienced where they actually intended to go.

The Worldspan service allowed Amtrak to take an ax to its in-house travel costs. Airfares plunged to $200 a ticket, from an average of $400. All told, Amtrak saved $730,000 a year on reduced air costs.

Amtrak got additional savings by tying Worldspan into its basic Ariba PunchOut purchasing system. But for a rail system with a billion-dollar deficit, a six-figure cost reduction is not going to make a big impact. Indeed, Amtrak executives, since the dance with death, are hard-pressed to point to any technology project that has delivered significant savings or revenue improvements.

Big Battle With Big Blue

Indeed, the biggest savings that Galey’s operation can cite are still to come. They’re due from a restructuring of Amtrak’s agreement to outsource much of its technology operation to IBM. When Gunn arrived in May 2002, Amtrak was in the eighth year of a 10-year contract—and Galey asked for permission to renegotiate.

Did Amtrak have any agreements that forced IBM to live up to any particular level of service? “Absolutely none,” Galey recalls. Did IBM insist on a logical architecture for Amtrak’s information systems? “For some god-awful reason,” he says, IBM put complex enterprise planning software from SAP on servers that ran the aging Windows NT operating system—and Amtrak’s databases on mainframe computers running industrial-strength IBM operating systems.

Plus, Amtrak would not be negotiating from a position of strength. “We didn’t know if we’d be in business in six months,” Galey recalls.

But the weakness may have been the strength. Not wanting to see a customer disappear, the integrator and consultant agreed to restructure the contract.

Now Amtrak has 100 agreements on the levels of service IBM must deliver, and the railroad also expects to reap $85 million in savings. Where before, Amtrak paid IBM $60 million a year, that is down to $48 million. The pact is guaranteed for four years and could be renewed for three more.

Key to resetting the terms, Galey says, was establishing that even if the ship was sinking, the hands on deck were knowledgeable and serious. The first shot across the bow: demanding that voice communications included in the deal be repriced, given plunging long-distance costs since the deal was originally signed.

“We laid the gauntlet in front of the 22-year-olds at IBM,” he says, “and they listened to us a lot more after that.”

Galey also didn’t allow lawyers into the discussions. He didn’t want to let the principals “lose control of negotiations,” he says. Once terms were reached, the lawyers could smith the words but not change basic intent.

In the end, Galey says, a restructuring takes faith in the other party. But not blind faith. You have to place that outsourcer in a position where its integrity is challenged, he says. And if the outsourcer lives through the challenge— in this case, that voice costs were unduly high—you go on with a deal.

Renegotiating also saved time, which Amtrak had little of, if it was to save itself. And it would not have saved a lot of money in any case. Working with the Outsourcing Institute of Jericho, N.Y., Amtrak determined that putting out its contract to competitive bidding might save $7 million over the course of 10 years. And that didn’t deduct the up-front costs of managing the competition.

Amtrak Technologies senior director Brad Burch, and a senior associate at the institute, Oliver Houck, determined over the course of seven months what the going rates were for, say, storing data on arrays of memory disks, and established how to monitor market rates after a new deal was signed.

But the main role of Houck and his firm was to establish how the new relationship would be governed. Under the first contract, Amtrak’s agenda would get lost through inattentiveness on the part of IBM, according to Houck and Galey. Even on-site, IBM’s employees would work on a different floor from Amtrak’s staff. “It became hostile,” Houck says.

Now the levels of service, such as response times at call centers, and even the level of attention from IBM senior managers are well defined. But defined or not, the new contract is not going to save Amtrak’s bacon. Even $85 million in one year is a rounding error in a billion-dollar operating deficit. And these savings are spread out over seven years.

Indeed, where Amtrak’s information systems conceivably could have their biggest impact is on increasing revenue, not saving money. Gunn is wont to argue that he has now cut operating costs to the bone.

But Amtrak still does not boast a yield management system that can rival those found in other transportation industries, particularly airlines.

Such systems figure around the clock what a seat is worth, with the value dropping to zero when a plane takes off or a train pulls out of the terminal. Even through the end of 2001, when he sat on the Amtrak Reform Council, the rail company’s revenue-maximization system “was one of the worst I’ve ever witnessed,” said Paul Weyrich, now president of the Free Congress Foundation, at a recent international policy conference.

“I dare say Bulgaria had better information systems for their railroad during their Soviet period than Amtrak did,” Weyrich said this past February.

Ignoring the Short Haul

Indeed, Amtrak management acted, in effect, to minimize revenue, not maximize it, he says. Under former president W. Graham Claytor, Weyrich says the rail line failed to publicize or promote short–hop travel on its routes, preferring to focus on higher-priced tickets from long trips.

To support the strategy, the company would set aside only a limited number of seats on a train, say 50, for “intermediate” trips. That meant lots of trains were running long distances full of open seats.

“They run a lot of empty trains because the management’s policy is precisely to discourage these intermediate trips,” Weyrich says.

Amtrak media relations director Cliff Black says Weyrich’s comments are off-base and not reflective of the sophistication of its current system. But he declined to make any executives available to discuss how Amtrak manages its passenger yields under the Gunn administration.

Black also says Amtrak needs around $1.5 billion from “outside sources, whether federal or not” to keep operating. In recent years, he notes, that has meant Amtrak has “borrowed heavily in commercial markets” to meet its needs, leaving it with a debt of about $3 billion and annual debt service of $270 million.

This “resulted from attempting to meet the unattainable mandate of ‘operational self-sufficiency,”’ Black says. That mandate, he adds, “has been shelved as a requirement.”

Now, he says, Gunn’s request for $1.8 billion is needed to “make up for years of deferred capital investment” in track, equipment and facilities. Part of the need? To repay a loan from the Department of Transportation, and pay the $270 million debt service.

For a sense of scale, Amtrak says it is spending in fiscal 2004 some $28 million on technology infrastructure, including an upgrade to its payroll system, investments in its Web ticket-taking system and improvements to its telephone call centers. By contrast, $196 million is being spent on overhauling its rail cars (a.k.a. “rolling stock”) and $117 million on paying off the principal on its borrowings.

“They do very creative accounting,” says Edward Hudgins, former director of regulatory studies for the Cato Institute. “The point is, the only thing that is going to stop this cycle is if Amtrak is privatized or declared bankrupt.”

Amtrak Base Case

Company: National Railroad Passenger Corp. (Amtrak)

Headquarters: 60 Massachusetts Ave. N.E., Washington, DC 20002

Phone: (202) 906-3000

Business: Runs nationwide railroad network for paying passengers.

Chief Information Officer: Robert D. Galey

Financials in 2003: $2.1 billion in revenue; $1.1 billion operating loss; $1.3 billion net loss; $1 billion federal subsidy.

Challenge: Improve quality of service, expand ridership and stay in operation while seeking higher federal subsidies in the immediate future.

Baseline Goals: