At 10 A.M. on a recent December morning, three dozen police captains, lieutenants and detectives assemble in a downtown Los Angeles wholesale merchandise market. Away from the grit of the city’s streets in a rented meeting room, these men and women hail from the San Fernando Valley police bureau’s six divisions, in the northern fringe of the city. Sporting dark blue police uniforms, jackets and ties, they eat over-sweetened pastries and drink weak coffee while they wait for the meeting to start.

They are participants in their bureau’s mandatory semi-monthly meeting, a key component of Compstat, which is a performance management approach instituted in 2003 by William J. Bratton, chief of the Los Angeles Police Department and former top cop in New York City.

Compstat, which stands for Computer Statistics, is a cousin of the real-time analytics systems deployed in corporations such as United Parcel Service and Wal-Mart. But this program is more than statistics. As Bratton describes it, “Compstat is a way of pushing power and responsibility down into the organization to the point where rubber meets the road.” It is the interplay of data analysis and management strategies that makes the program so powerful, he says.

QUESTION: What did it take to create a successful data analytics program in your company? Tell us at [email protected].

QUESTION: What did it take to create a successful data analytics program in your company? Tell us at [email protected].

Though large companies increasingly use analytics software, most businesses haven’t adopted a comparative real-time analytics system, says Robert Blumstein, a research director at research firm IDC. That’s because some executives doubt the value and expense of real-time analytics.

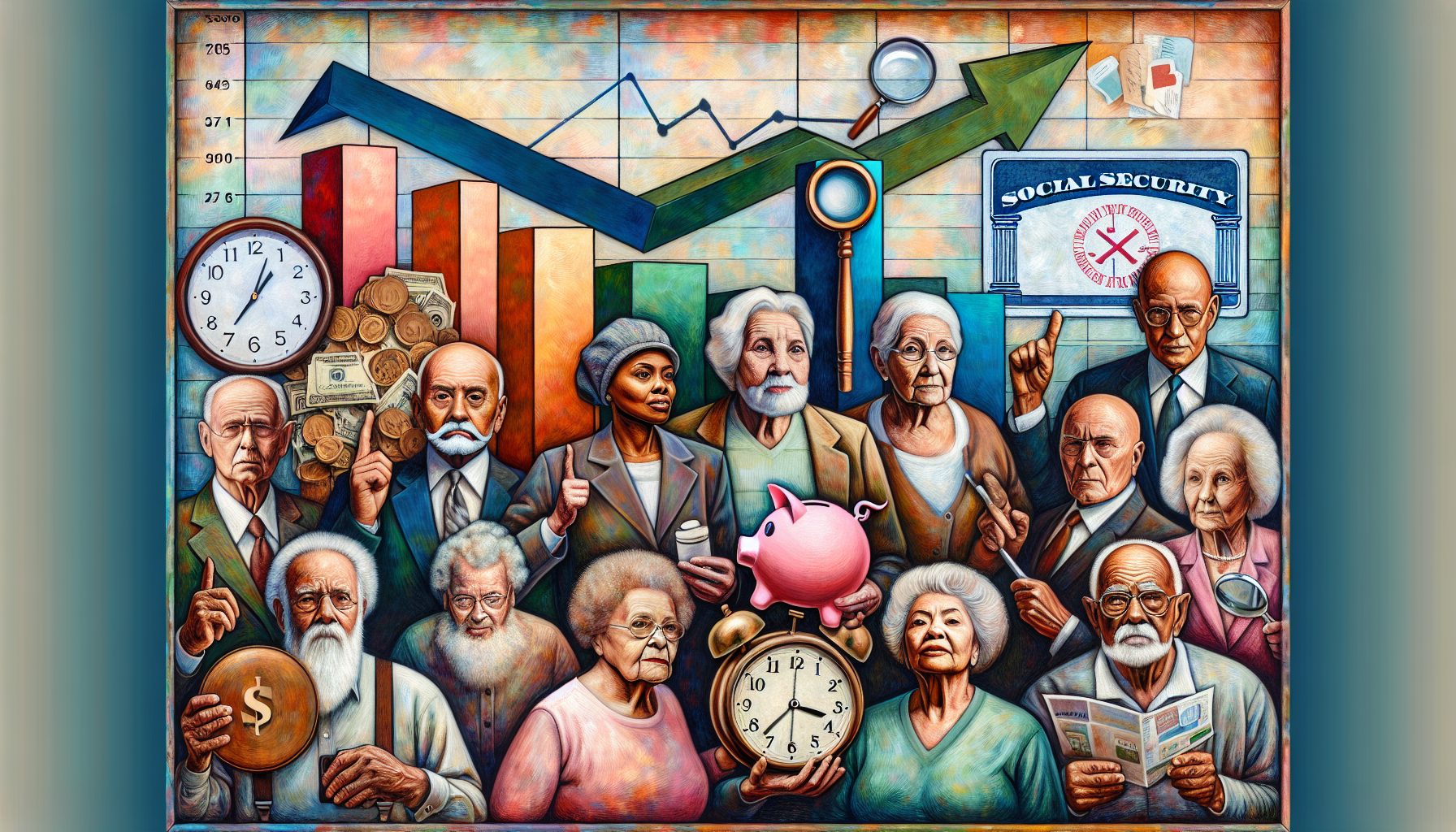

Bratton faced such skepticism in New York, where he implemented Compstat in 1994. There was an entrenched belief at the NYPD—and other police departments—that crime could not be prevented no matter what analysis systems were thrown at the problem, according to Dennis Smith, associate professor of public policy at New York University’s Robert F. Wagner Graduate School of Public Service. And when serious crime in that city dropped by 25% and homicides went down by 44% during Bratton’s 27-month tenure, critics attributed the decline to population shifts and an improved economy. Naysayers notwithstanding, crime in New York has dropped by 69% in the last 12 years.

Convinced that Compstat was the catalyst for New York’s crime drop, Bratton set out to prove that the approach could be effective in yet another city—in this case, on the West Coast. Since the inception of Compstat in L.A. three years ago, combined violent and property crimes have dropped by more than 26%, outpacing the nine largest cities in America for the same time period. The numbers are particularly striking considering there is one police officer for every 426 Los Angeles residents, only about half as many as in New York and Chicago.

The LAPD’s ability to rapidly gather and evaluate crime statistics offers insight into how a large, bureaucratic organization can dramatically improve key metrics by vigilantly and systematically monitoring, analyzing and acting on information.

While most companies aren’t in the business of saving lives, those that do manual analysis are at a competitive disadvantage, says IDC’s Blumstein: “Fewer decisions can be made that way, and more slowly. It doesn’t allow companies to operate in a nimble manner in an environment where the marketplace is changing and new products are regularly introduced.”