For humanitarian organizations such as Catholic Relief Services and CARE that bring food, medical care and other assistance to places like Africa, good communications network improve their ability to coordinate relief efforts, reorder supplies, and report problems and progress back to their home offices. But simply securing communications lines in developing nations can be a major challenge.

The problem is not only that local telecommunications services tend to be scarce and unreliable. Local governments also tend to thwart potential solutions, even for organizations that are there to help their people.

Quophi Yelbert, a regional technology manager for Catholic Relief Services (CRS), recalls having to cancel a contract with a satellite-based Internet service company that would have provided greater network connectivity to the agency’s office in Liberia. “The government wanted $1,500 per month for licensing, and we were only paying $500 for the bandwidth,” Yelbert says. In Burkino Faso, another West African nation, CRS has been forced to obtain licenses for any sort of wireless communication, even on frequencies designated as license-free by the International Telecommunication Union, he says.

To avoid these headaches, Yelbert tries to find local “turnkey” service providers that can take care of both the bandwidth and the bureaucracy.

Ted Jastrzebski, senior vice president of finance, information technology and administration at CARE USA, reports running into problems similar to those faced by CRS. “Some of governments have very tight telecom regulations that might not allow us to implement what we consider the best solution, or even the most cost-effective solution,” he says.

CARE, for instance, was unable to complete its plans for a satellite communications network link in Ethiopia. “We thought it would be just a matter of having some discussions with the government, and we would have the problem solved for this country. But it turned out to be not so straightforward,” Jastrzebski says, because authorities wanted CARE to use the national telecommunications company instead. “Our ideas just were not in sync with the government’s agenda.”

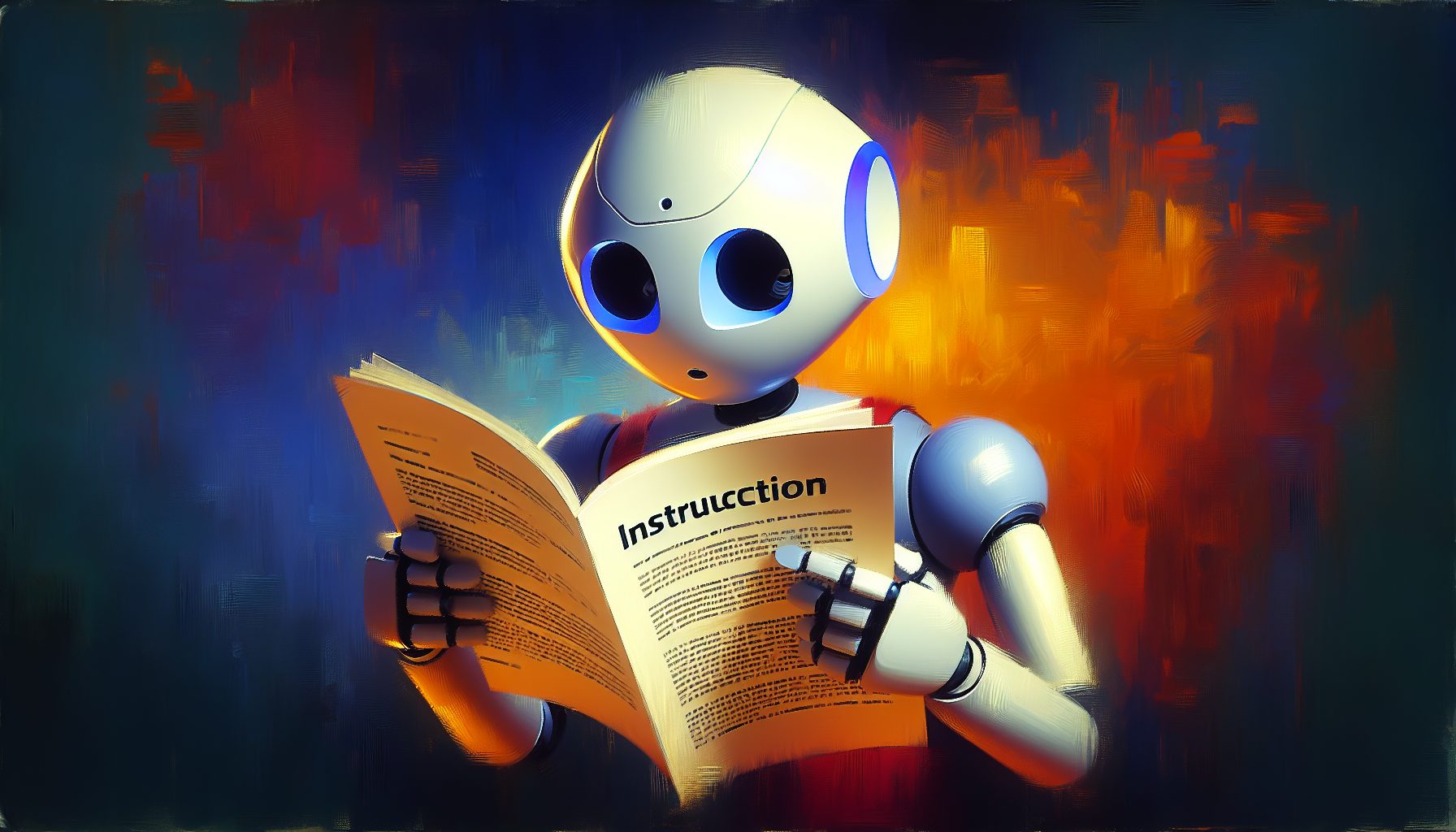

The volume of details that field officers need to send back to headquarters is enormous. A food distribution plan, for example, needs to include things like how much is needed and where, who will meet the ship at the dock, where the food will be warehoused and how it will be transported.

During a crisis like a famine or an outbreak of war, “the demand for information by headquarters becomes voracious,” says Paul Cunningham, CRS’ management information systems director. That’s when the charity’s directors start clamoring for information on the overall situation, changes in operational status, and the safety and welfare of personnel.

“Three years ago, it wasn’t so important if the link was down for a few minutes,” Yelbert says. “But as the links become more reliable and people make more use of e-mail, people become more reliant on them.”

Both CRS and CARE are exploring ways they can provide more reliable bandwidth to their field offices. For example, the two agencies are participating in NetHope, a consortium partially underwritten by Cisco that is seeking to establish better network infrastructure for use in developing nations. NetHope assists humanitarian groups in defining network architecture, gathering requirements, soliciting bids and establishing contracts with competent local providers. Its goal for the first half of 2004 is to establish high-speed Internet access at more than 100 locations in 40 countries.

Another way CRS is looking to improve communications is with voice-over-Internet Protocol (VOIP) technology for economical international phone service. For example, since VoIP service was introduced in Macedonia, the CRS office there saved $2,300 over 12 months. By avoiding expensive international calling charges —not only to headquarters but to offices in neighboring countries—CRS workers also are able to talk longer “without necessarily watching the clock,” Cunningham says. However, the technology is only practical at locations that have good Internet connections. In Sierra Leone, for example, CRS uses a radio-based Internet service that doesn’t provide the kind of fast, reliable connection needed for voice communications.

Indeed, there will always be limitations on how far into the field these organizations can extend their networks.

The key, according to Cunningham, is to keep things simple. Sure, providing handheld computers and wireless connections to food distribution crews would be more technically elegant, but a pen-and-paper system is more practical for the places they go. “We have to remember we’re not an I.T. organization,” he says, “we’re a humanitarian organization.”