Cracking down on fraud in the food stamp program has long been an objective for the United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Beginning in the 1990s, when the agency migrated to benefits cards, it has used some form of analytics to detect suspicious patterns and home in on those abusing the program.

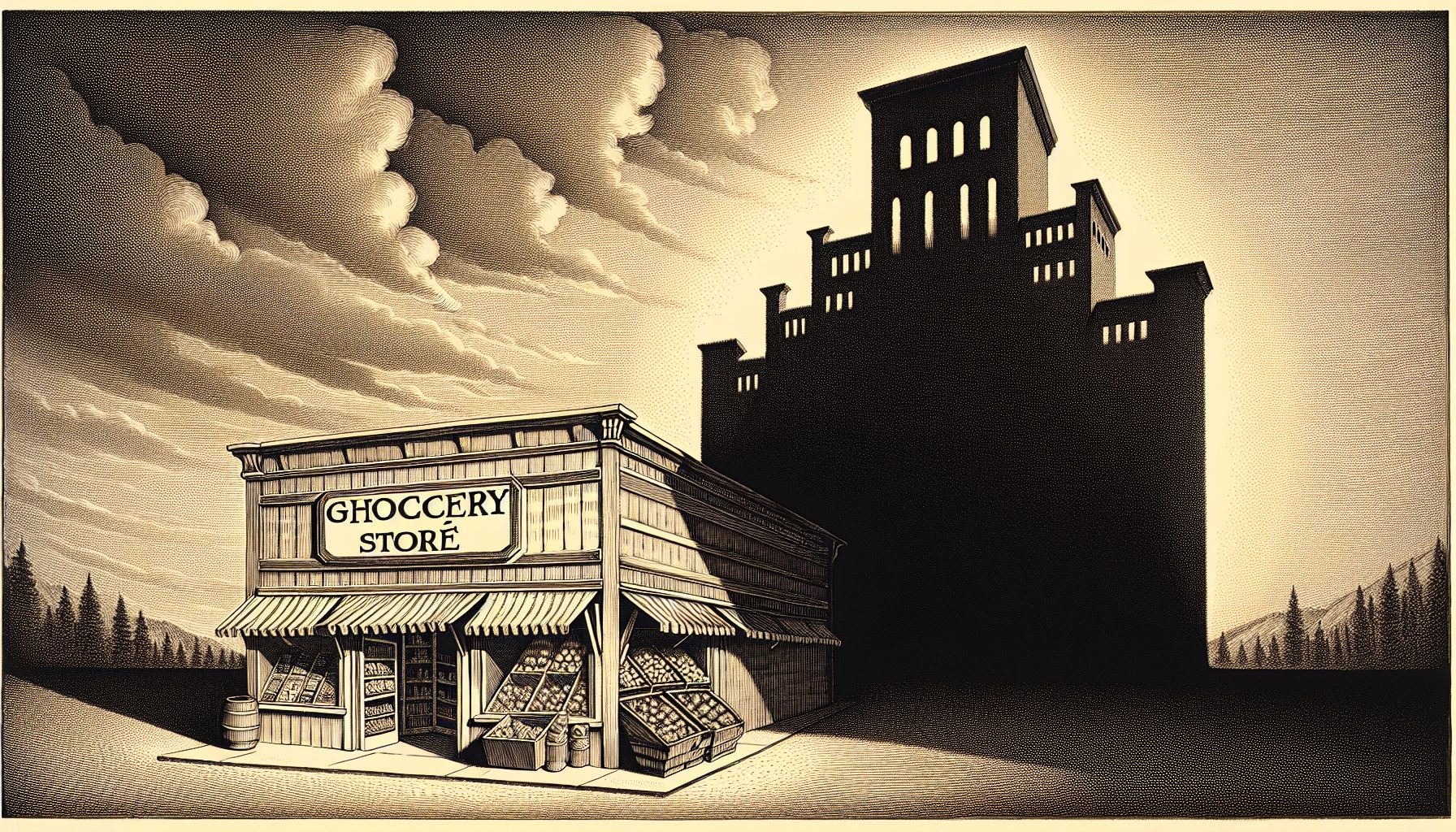

However, the agency’s Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) has recently stepped up efforts to root out abusers by focusing on stores and individuals engaged in trafficking Electronic Benefit Transfer (EBT) cards and skimming cash. For instance, in some cases, a store will hand over $50 in cash for a $100 card, which is supposed to be used to buy food items.

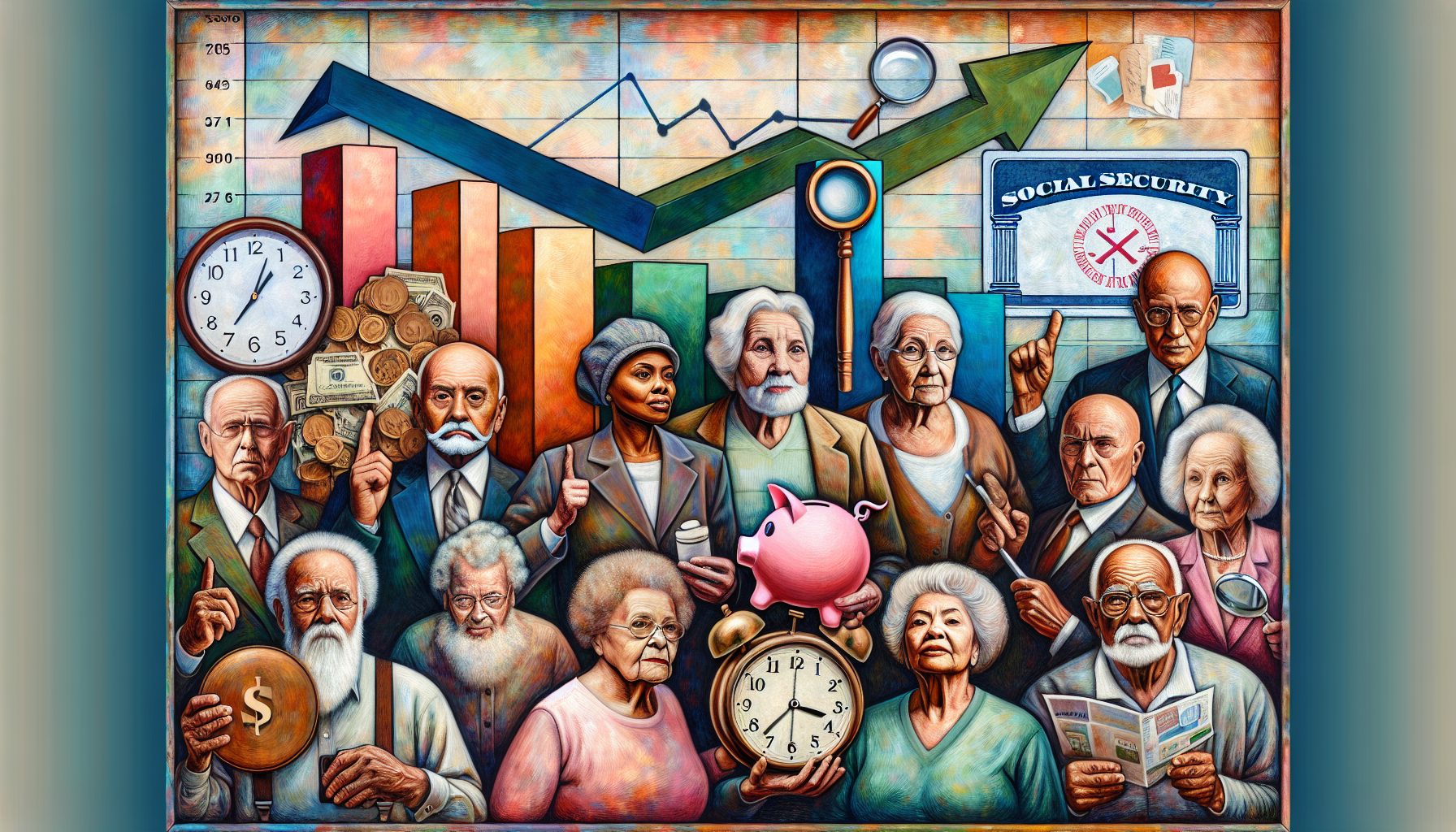

The federal government does not directly administer SNAP benefits and programs—the states are responsible for that task. But the USDA is responsible for monitoring stores and preventing fraud in the $74 billion program, which serves about 46 million Americans.

“We authorize stores, we approve transactions and we investigate if we find any indication of wrongdoing,” explains Ronald Ward, director of the Program Accountability and Administration Division for the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program at USDA’s Food and Nutrition Service (FNS). Building on best practices culled from two decades of analytics, the agency is now expanding its capabilities and sharing its expertise with the states.

Turning to Advanced Analytics

FNS, with assistance from Accenture, has turned to advanced analytics software from SAS to spot possible fraud, which typically occurs at smaller urban and rural stores. When it catches a store cheating, FNS dispenses penalties ranging from a 12-month disqualification to permanent exclusion from the program, depending on the severity of the violation. Individuals can also receive penalties, including a loss of benefits.

“We now have the ability to sift through tens of thousands of transactions per month and data mine them for patterns,” Ward reports. “When you’re talking about an individual, it’s tougher to spot fraud because there are fewer transactions. However, at a store, a higher volume of transactions allows us to build strong predictive models.”

The Food and Nutrition Service collaborates with states to share best practices and improve fraud detection. One of the first states it collaborated with was South Carolina. Once it began using the FNS predictive model, the state’s detection and disqualification rate rose from about 60 percent to 83 percent. Among other things, “This means that they are able to devote resources far more effectively,” Ward says.

FNS has now expanded the program to Pennsylvania, Kansas and Texas, along with several counties: Onondaga County in New York, Milwaukee County in Wisconsin and Sacramento County in California. The biggest challenge, he says, has been ensuring data integrity and introducing standardized methodologies, particularly because different state and local agencies use different systems and databases. FNS sends other government agencies batch data, which they put to use locally.

A key to success, Ward reports, was focusing data scientists on smaller and more manageable tasks before expanding the scope of the analytics program. “It was important to demonstrate quick wins and show a return on investment before moving forward,” he points out.

FNS plans to continue expanding the program and working with its staff of data scientists to improve the underlying algorithm further.

“Some states have brought in vendors and attempted to build programs, which are often expensive and less effective than desired,” Ward says. “But we are seeing real-world results with this program. It’s helping put tax dollars to work more effectively.”